Of the practitioners surveyed, 51 per cent stated they do not use an active, standalone database within which their empty homes data is stored or monitored. This may not be directly linked to the determination of the council tax-base submissions being accurate as mentioned previously, although the development and implementation of such database could enable practitioners the ability to accurately report statistics in the future.

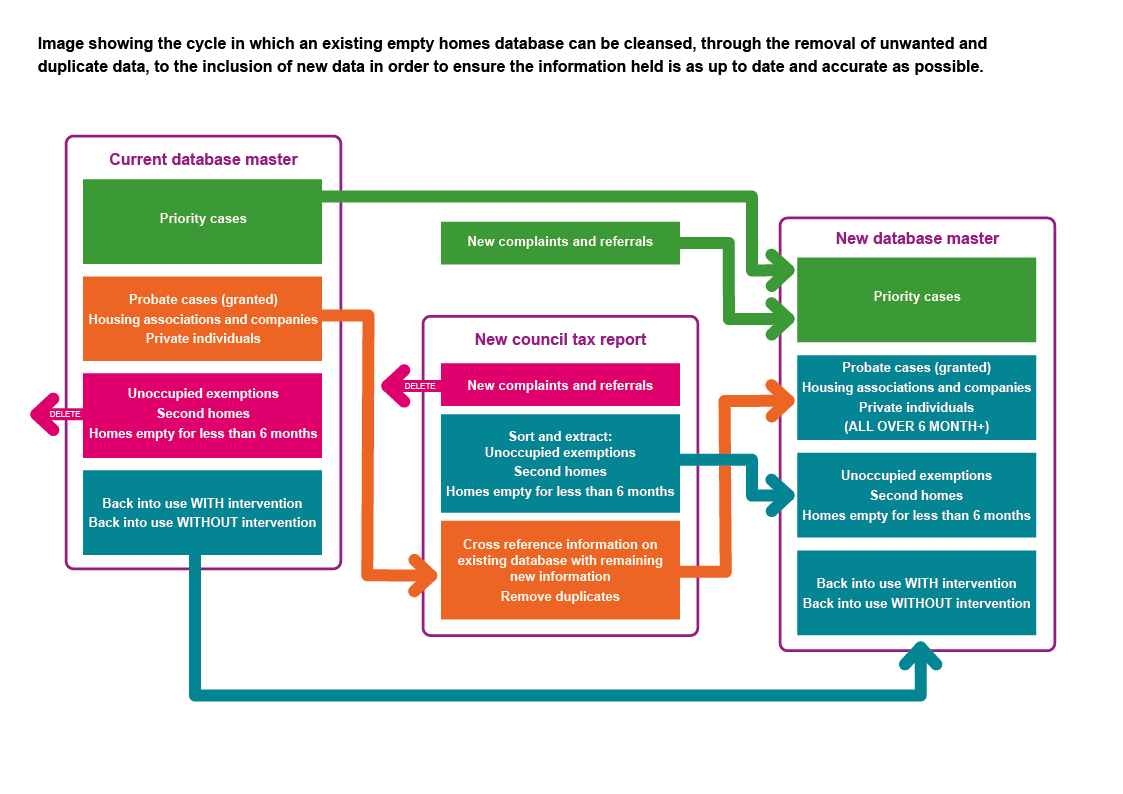

The theory behind the implementation of a standalone database works on four key principles:

- the storage of relevant and accurate information

- the tracking and monitoring of statistics

- efficient categorisation of data to carry out targeted mail merges for engagement and data cleansing

- effective prioritisation of workload.

From a practitioner’s perspective, a database works on the premise that all information concerning any type, class or category of empty home is recorded. Separate from a council’s content management system, such as Uniform, Civica or Tascomi, the database provides an ongoing working document from which cases can be monitored, categorised or recorded as brought back into use with or without intervention. Using a simple Excel spreadsheet, all empty homes are recorded across each of the wider definitions.

A standalone database also has several ongoing benefits:

- statistics are easily accessible and broken down for the purposes of reporting to senior management or corporate documents,

- trends and patterns can be quickly identified

- by categorising the data on properties, workload priorities can be quickly determined.

However, the largest benefit is through the layout and structure of the database. By separating the database into categories, large scale data cleansing through mail merging can allow for correspondence to be targeted and tailored to the target audience.

Crucially, the database is centred around four primary categories or ‘tabs’ of empty homes:

- priority cases

- probate cases (those with probate granted and their subsequent council tax exemption elapsed)

- properties owned by housing associations and or companies

- private individuals.

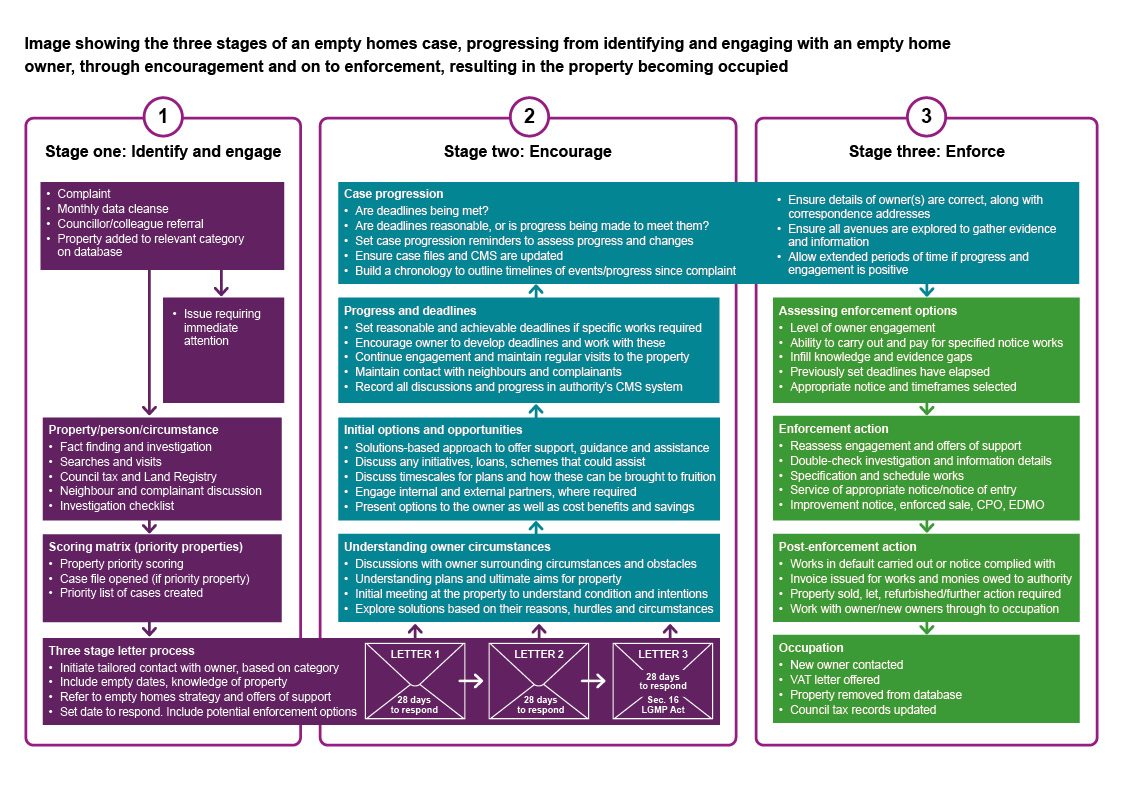

Based on a council’s prioritisation of how they would focus efforts on their empty homes work, the priority cases could comprise of cases where complaints are registered, the longest-term empties, the properties in the worst condition, or those with active casefiles open. However, the structure of the database allows for properties across all categories to be moved into the priority tab at any time. Those that are showing as being priorities, are then mirrored in the council’s CMS system where case files, documents and interactions are recorded on an ongoing basis. This is limited to priority properties only, as opening such files on a CMS system would prove too large a task to carry out, and the natural return to use of some empty homes would often mean a case file being closed with no input being required.

Additional to the above four tabs or categories, the database includes separate tabs for recorded empty homes across the wider definition, these being less than six month empty homes, second homes, and unoccupied exemptions. Whilst these tabs are not expected to warrant the same engagement and investigation levels as the previous four, the inclusion of them can allow for all empty homes statistics to be monitored. Where one of these categories presents what an authority would consider a priority case, the information held can easily be transferred into the priority tab. It also allows for full data sets in a set standard format to be used in a large-scale data cleanse or mail merge. Holding such data also presents further benefits for the local council and the empty homes officer, for the purposes of conducting further proactive work.

Information held on properties empty for less than six months, can provide an insight into the number of properties passing the 6 month threshold in the following month’s or future data cleanses. This can prompt a proactive mailshot to such owners to outline the council’s activity on empty homes, begin offering their services and support, but also pick up properties where owners have since moved into a property but where the council tax account is still shows it being empty. Theoretically, this should ensure that only the genuinely empty homes are eventually input into the database. This tab however, does not go through the same cyclical data cleanse carried out for the standard categories and tabs.

With regards to second homes, the introduction of a second homes premium would outline the numbers of such properties in a council’s operating area, but also enable an officer to carry out proactive steps as mentioned above in outlining the premium and how the authority can support them in selling or renting the property, prior to the second home premium being applied. These properties, as with all other cases, can be transferred into the priority case tab should a complaint or situation arise where the property warrants more intensive and focused action.

Finally, the unoccupied exemptions containing all further properties known to be empty, albeit for a valid reason, can be shown within a further tab and actively pursued based on their known circumstances for exemption. As with all other categories in the database, the additional breakdown of categories within this tab will be based on their exemption class, with targeted and tailored letters sent to each class exemption based on their reason for being empty. For example, properties with an exemption due to the owner being deceased, would be written to or contacted slightly differently to properties that have been repossessed by a bank or financial institution.

To complete the database, two further monitoring tabs are included to allow officers to move and record properties brought back into use both with intervention, and without. By simply cutting the information from any of the primary database categories and inserting here, these monitoring tabs will allow easy referencing to officers enabling them to track numbers of properties brought back into use through their activity.

Within each of the tabs, the columns will represent the different aspects of the case being investigated. Here, it is suggested that the probate, housing association or company and private individual tabs hold standard information already supplied by Council Tax. This includes empty address, postcode, empty date, and any forwarding address details for the owner or liable persons. However, the priority tab showing the cases where action is more intensive, further columns will include more detailed information about the property, the person and their circumstances. This can include dates of letters sent, next actions, other known addresses, council tax or council debts as well as notes, comments, and links to planning applications and estate agent pages where a property is for sale. Not intended to be a comprehensive or extensive notes page or case progression tool, the depth and quality of the information will allow an officer the ability to have all relevant and detailed information in front of them if and when the time arises that engagement with an owner begins.

Whilst information gathered to this extent is not necessarily required in the other primary or additional tabs, a case can be transferred to the priority category and information subsequently obtained to be include in the relevant columns as information and evidence is gathered.

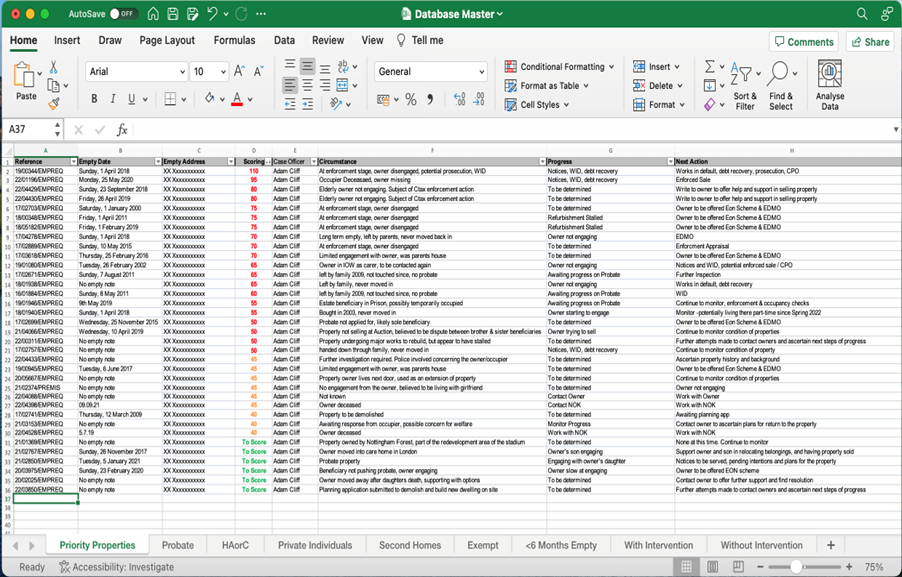

Empty homes database example

The database example shown here, shows the information and data columns across the top of each of the spreadsheet tabs, with the standard information columns present in all categories and tabs. The additional columns, showing more detailed information on cases, are present in the priority properties tab only. The primary tabs are located along the bottom, followed by the additional and monitoring tabs.