Resetting the relationship between local and national government. Read our Local Government White Paper

Inadequate, poorly planned and unfair: adult social care funding in England since the Care Act.

Ten years on since the Care Act received Royal Assent in 2014, adult social care in England remains fragile and fragmented. In large part, the ambitions of the Act to establish a clearer and fairer system of care and improve people's independence and wellbeing have been undermined by central government's approach to funding social care.

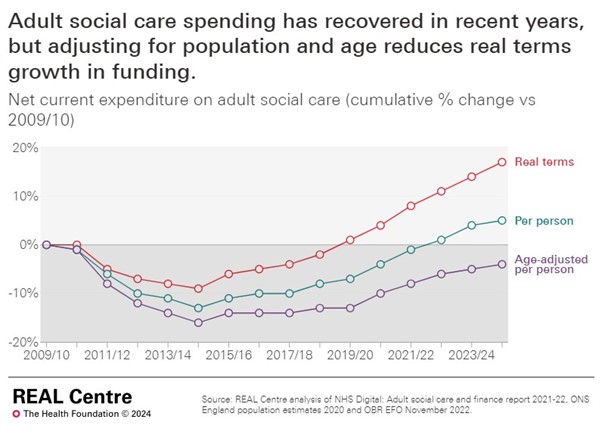

For years, social care has faced demand pressures from an ageing population, growing prevalence of disabilities, changing societal expectations and increasing costs of care. But funding has not kept pace with these pressures. Adjusting for age, spending per person on social care in 2024/25 is 4 per cent lower in real terms than in 2009/10. This is despite a recovery in spending following significant real terms cuts leading up to the introduction of the Care Act, which particularly affected deprived areas. And this likely underestimates pressures since we do not account for factors like increasing care need among younger adults.

In the absence of sufficient long-term funding for social care, councils have become increasingly reliant on last-minute and time-limited national grants to prop up the care system.

Piecemeal funding has created uncertainty and made it harder for people who provide and draw on care services to plan ahead. Another troubling consequence of this short-termism is the lack of progress on ambitions to provide more preventative services and support more people to live longer at home.

Short-termism has also resulted in much needed funding reforms being shelved yet again. In 2021, the government announced new funding for social care to finally implement charging reforms including a ‘cap’ on lifetime care costs, many years after the Care Act first legislated for them. The following year, these reforms were delayed (not for the first time), and a limited set of planned changes to improve staff training and technology were watered down. The government announced that money earmarked for reform would instead go towards current pressures on care services, continuing the legacy of short-termism. In total, the Department of Health and Social Care reallocated over £1 billion of system reform funding to other social care priorities between 2022-23 and 2024-25. The redirection of these funds in favour of sticking plaster measures reveals a lack of political will to address systemic problems in social care.

In this precarious context, central government has devolved greater responsibility for raising social care funds to councils. In 2016, government introduced a social care ‘precept,’ giving councils the option of increasing council tax to raise additional funds exclusively for social care. This move has increased inequalities between areas, as more deprived councils cannot raise as much revenue from the precept as more affluent ones. Compared to national grant funding, the precept is not as targeted towards local need. It has also added another layer of complexity to an already convoluted funding landscape and passed political choices about increasing taxes to fund social care onto councils, when they are grappling with strained budgets.

The government’s approach to funding social care over the past decade contrasts with spending on the NHS. Just like social care, NHS funding has not kept pace with need and has also been subject to short termism. But the NHS budget was relatively protected from cuts compared to other public services and has seen some more strategic funding, including a five-year funding settlement in 2018. Differences in government policy and funding between social care and the NHS undermine ambitions to join up services, while challenges in social care have a knock-on impact on health services, contributing to problems with timely discharge from hospital.

The impact of the approach to social care funding since the Care Act on people’s care is clear:

- Repeated failure to fund long term reform to the charging system for social care means that the system remains a threadbare safety-net, with publicly funded care only available to those with the highest needs and lowest means, leaving many people facing catastrophic costs.

- Access to support has eroded: fewer people received publicly funded long-term care from councils in 2022 than in 2015, despite more requests for support. Councils report high numbers of people waiting for care.

- Pressures on budgets drive down the fees councils pay care providers and the wages of care workers, contributing to sustained staffing problems. Despite care worker pay increasing since the introduction of national living wage in 2016, the sector continues to be low paid and the average care worker was paid less than sales and retail assistants in 2023.

- People who pay for their own care often face eye-watering fees, partly since providers typically charge them more to make up for the lower fees paid by councils for those who are publicly funded.

- Funding pressures make it harder for providers to improve care. While most people receive good care the CQC continues to find unacceptable instances of inadequate care and abuse.

Social care funding is conspicuously absent from the pre-election debate but politicians must take it seriously. Even more people will need social care in the future as we live longer with major illness and disabilities. Our social care funding analysis estimates that an additional £8.3bn per year would be needed by 2032/33 just to meet expected growth in demand from an ageing population. This would not be enough to improve people’s care and meet the decade-old Care Act ambitions.

Meaningful reform will require more money. We estimate that it could cost an extra £18bn by 2032 to meet growing demand for care, enable more people to access publicly funded care, and improve services.

The next government will face tough spending decisions but it must break the pattern of inadequate, poorly planned and unfair funding in social care. Where there is political will, there is a way to provide better, fairer and more generous support for disabled and older people and their families.