It is clear the current system has much room for improvement, so local government leaders are always seeking to find innovative ways of improving the design and delivery of skills and employment support in their local area. Whether supporting people or employers, councils and combined authorities are striving to do the best they can to level up opportunity across the country.

Supporting businesses

Councils and combined authorities are committed to supporting businesses to access the skills they need to recover from the pandemic and are to tap into emerging industries such as digital and green that will be increasingly important to employers and investors.

Case studies: meeting employer need

By 2030 Harlow may need between 6,000 and 14,000 battery electric vehicles (EVs). The Essex County Council-led pilot is supporting the transition from fuel-based to EVs including a new Electric Vehicle Centre at Harlow College, opening in September 2022. The project will fund 50 free places over a 24-month period for Automotive Technicians to develop the skills and knowledge to maintain and repair EVs, futureproofing local employers. Community learning workshops will raise local awareness about the benefits of EVs and provide EV owners opportunities to understand more about their vehicle including safety awareness. With more funding, they would extend this to include training courses to upskill electricians to install or maintain council-owned charging points.

Babergh & Mid Suffolk Councils’ Innovate Local is a multi-project initiative offering affordable spaces to start-up businesses alongside a digital skills programme which is now expanding to target those wishing to return to work after a career break.

Tees Valley CA is developing the Teesworks site, the UK’s largest industrial zone, into a hub for future job creation centred around advanced manufacturing, innovation and clean growth that would generate 20,000 jobs. As it is an area with low skills and high unemployment, the CA is working hard to ensure employers recruit local people with the right skills. In 2020, it launched ‘Teesworks Skills Academy’, a consortium of colleges and training providers. Within six months, more than 1,000 local people registered their CVs and more than 200 took up training. It is accessed via the local employment hub, run by Redcar & Cleveland Borough Council.

Redcar resident Jordan Taylor, 30, was one of the first to progress through the Teesworks Skills Academy. He registered in April 2021 and completed a ‘routeway to scaffolding’ course with provider Neta Training Group. He achieved six qualifications and now works for a Middlesbrough scaffolding firm. Redcar & Cleveland Council’s training and employment hub helped him access a bike and a train pass so he could get to work. Jordan said: “I’ve worked all my life, so when I found myself unemployed, I wanted to get straight back into a job. It only took a few weeks from me signing up to the Skills Academy to being placed on a training course so I could gain some new qualifications and get another job. The whole process was spot-on – it was easy, friendly and fast.”

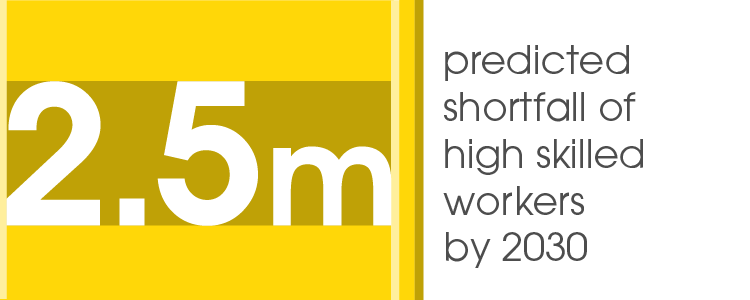

Skills are critical to meeting our labour market needs, and the Government has invested in and reformed part of the system including the free Level 3 provision (A-Level or equivalent), a National Skills Fund which enabled bootcamps, FE planning reforms and a lifelong loan entitlement for level 4 and above. Investing in Level 3 will support many, but the 9 million adults in England lacking functional literacy and numeracy skills will not benefit, nor will the 13 million UK adults not qualified to Level 2 (GCSE or equivalent). Equally important is unlocking talent through English for Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL) and helping citizens become more digitally proficient to get on in life and work. The least qualified are unlikely to engage in learning, yet most likely to be in low-paid work, and suffer job loss, so helping adults progress from community-based, pre-entry learning through to Level 2 is vital. Devolved Adult Education Budget has led to a more coherent adult learning offer, augmented the local offer and improved participation.

Case studies: devolved AEB

Liverpool City Region is using devolved AEB to address progression route gaps towards Level 3. It is supporting WEA with a Test and Learn pilot to help residents gain a bespoke Level 2 Maternity Nurse qualification with the aim of progressing towards the industry required standard of Level 3. Some MCAs found that sections of their foundation economy would not benefit from the national list of economically viable approved free Level 3 qualifications, so used their devolved AEB to widen access to supplementary qualifications, supporting more people to upskill.

Cambridgeshire & Peterborough Combined Authority (CPCA) used its £12 million allocation to increase participation by nearly 10 per cent (2020/21), targeting low-skilled residents in deprived areas (Fenland and Peterborough), introduced a £1,200 bursary for Care Leavers aged 19-22, fully funded ESOL) the first level 2 and 3, as well as the second level 3 for priority sectors and unemployed people.

West Midlands Combined Authority stewarded a 33 per cent increase in provision aligned to regional priority sectors (such as construction, manufacturing, digital and business and professional services), introduced new ways to support people in low-paid, low-skilled work. For instance, providing ‘Access to HE’ for ambulance contact centre staff to progress to paramedics, Level 4 care management for Black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) workers, and construction management for women.

Supporting people

It is difficult for any employment support provider working to DWP’s large CPAs to know what combination of support a long term unemployed person needs in a specific location spanning a CPA Swindon to St Ives (230 miles apart), or Chester to Carlisle (130 miles apart). This often results in capacity issues, with providers having to prioritise areas or people which will give them the quickest outcomes, and capability issues where providers may not have the local knowledge of a vast spatial area, so often need to work with councils or sub-contract to draw in local providers. Joined up services are critical to support some groups back into work, especially long-term unemployed people that may need support including housing, skills and financial management advice, and those with long-term physical and mental health issues who may struggle to get into, retain and progress in work which affects their confidence, pay, living standards and productivity.

There is a growing awareness of the relationship between health and prosperity, with differences in health helping to explain productivity gaps between places. The Levelling Up White Paper rightly stresses the link between people’s health, education, skills and employment prospects and focuses on policies to ensure everyone, wherever they live, has the opportunity to lead healthy and productive lives. The forthcoming Disparities White Paper and the Cross Government Forum on Health Disparities should offer more place-based solutions. Where local government has more flexibility to work hand in hand with providers from the outset, there are positive outcomes.

Case studies: supporting people into work

Greater Manchester Combined Authority’s (GMCA) ‘Working Well’ suite of devolved and test-and-learn employment and health related programmes, take a whole-population approach to health, skills and employment. To date, these programmes have supported more than 60,000 people, helping more than 15,500 into work - a success rate of 26 per cent. Crucially provision also supports inactive groups. GMCA recognised from the start that to turn Greater Manchester into a ‘northern powerhouse’, it had to tackle the very high level of economic inactivity, and particularly health-related economic inactivity. It was also a key element of the health and social care devolution deal.

Central London Forward’s £51 million devolved ‘Work and Health’ programme, ‘Central London Works’, aims to support 21,000 residents with health conditions and disabilities and the long-term unemployed into work. Not only do CLF and Ingeus, the provider, work closely to assess referral numbers, job starts, and the quality of jobs and support, they work with the boroughs to integrate borough-led and JCP provision including through ‘super centres’ in Hackney, Lambeth and Islington, which also helps to support employers’ recruitment needs.

Tees Valley and DWP ‘Routes to Work’ pilot helped 4,000 people furthest from jobs prepare for, and access work through its local employment hubs and secured work for 800 across the region. Despite its success, it ends in March 2022, making way for ‘Restart’ delivered by a new provider and requires building new client / provider relationships.

Northumberland Council’s ‘North East mental health trailblazer’ on behalf of seven councils piloted integrated employment support and talking therapies to unemployed people with anxiety and/or depression, to improve their mental wellbeing and help them find work. Over 1,450 people were supported, with more than 270 moving into work, showing these services could work together, but funding ended, so the work discontinued.

Ensuring all residents have access to training and jobs is essential. Understanding inequalities and barriers that some groups face when accessing skills or employment is key. Local areas will have their own inequalities based on protected groups (such as disability, ethnicity, age and sex), socio-economic status, rural isolation, veterans, care leavers and any other inequalities that may exist in a community. Local interventions target provision more effectively as it has a greater understanding to the nuances in local inequalities.

Case studies: addressing inequality

Bristol City Council's Stepping Up Diversity talent leadership programme included a spin off targeting Somali women, based on local data. It resulted in a 60 per cent increase in career movement, as well as an increase in confidence.

In West Yorkshire, Leeds, Wakefield and Bradford councils used devolved underspend from the national Youth Contract to bridge existing services and providers together, rather than create new provision. This helped three in five young people (57 per cent) into education, training or employment, while nationally contracted provision supported 27 per cent. Funding was time-limited so the scheme ended. Since then, West Yorkshire Combined Authority’s Employment Hub supports 6,000 young people. The Hub is locally delivered and branded, and offers integrated support bespoke to individual council areas.

Durham County Council's DurhamWorks partnership aimed to support 10,000 16-24 young people not in education employment or training from 2016-2021 through an integrated employability and wider support offer. 2018 interim analysis showed that for every £1 of investment, £2.69 of social and economic value has been generated (based on an investment of £12.3 million).

There is a continued role for councils to act as the ‘middle tier’ in local education systems, between the DfE and schools, irrespective of school structures. As the Government retains an ambition to see every school become part of a strong Multi-Academy Trust (MAT), in a fully academised system councils would be ideally placed to bring together their existing duty to promote wellbeing of all children with place-based leadership as well as synergies with their wider role around safeguarding, public health, criminal justice, employment, skills and cohesion. We would also like to see children and young people have access to a broad curriculum within local schools that includes vocational courses and skills that would benefit both pupils and the skills needs of local economies.