Introduction and context

As part of the UK’s transition to net zero, transport emissions need to be addressed. The UK Government is committed to a transition away from internal combustion engines (ICE), with a ban on the sale of new petrol and diesel vehicles in 2030, with hybrids to follow in 2035. It is anticipated that this will cause a step change in uptake of battery-electric vehicles (BEVs) which currently make up less than 1% of vehicles in the UK. The Government’s Transport Decarbonisation Plan, puts electrification of cars front and centre of the UK’s net zero ambition.

To support BEVs new charging infrastructure is required, and there is likely to be a role for the public sector in ensuring the required infrastructure is delivered, and that it meets the needs of residents. Therefore, the Local Government Association (LGA) has commissioned Local Partnerships to carry out a research project into the role of local authorities in delivering the electric vehicle (EV) charging infrastructure.

The focus of this work is on the charging of private cars and vehicles in residential areas where there is no off-street parking (i.e. on-street charging). The purpose of the work is to inform the LGA’s approach to discussions with Government and to identify any areas where it would benefit members for the LGA to provide support or guidance.

Findings

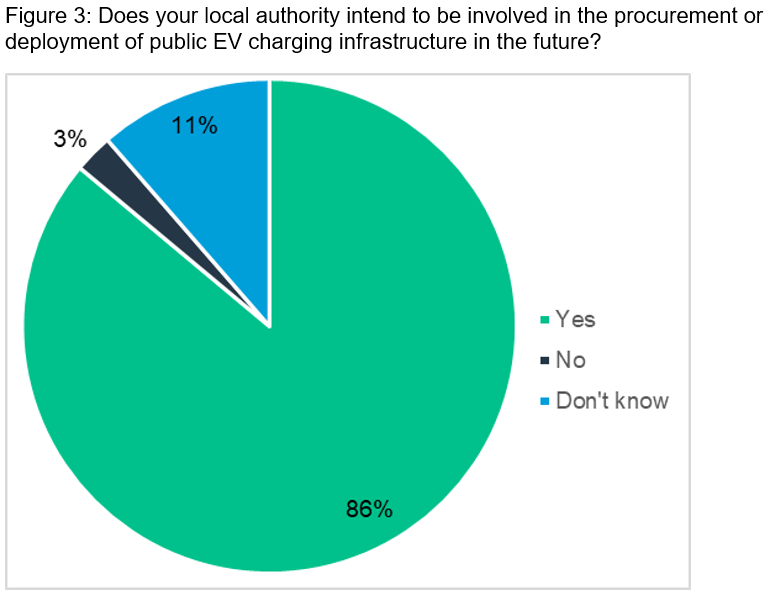

In most areas local authorities have delivered some EV charging infrastructure, although some of this is historic or legacy infrastructure dating back some years. Most authorities are planning to be involved in the procurement or deployment of public EV charging infrastructure in the future.

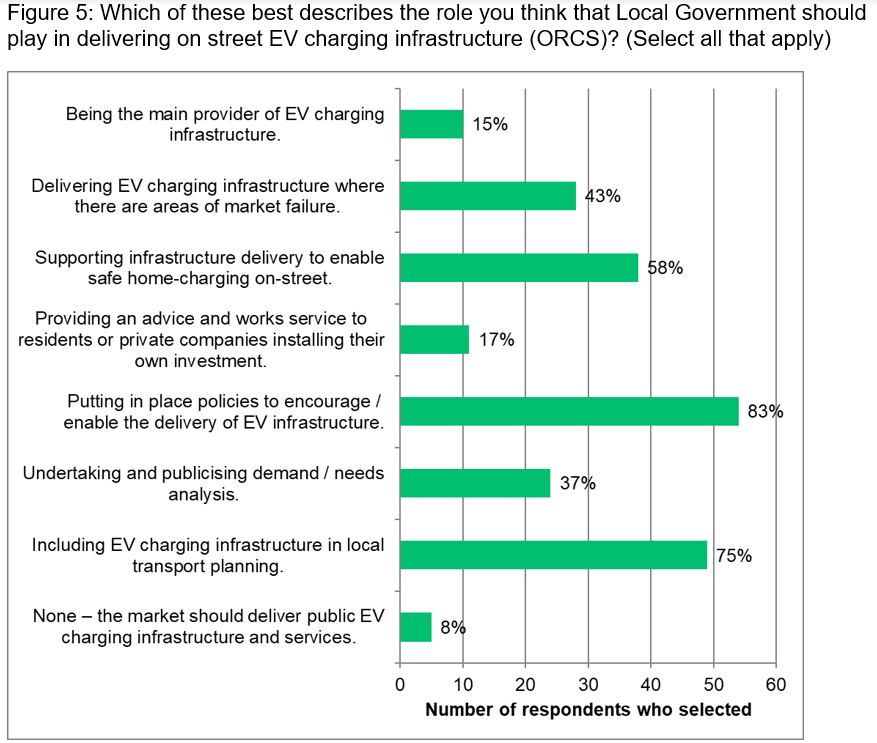

Currently the role for local government in the delivery of EV charging infrastructure is not clear and many local authorities feel that they lack the appropriate skills and data to make investment decisions in what is seen as a fast-paced and evolving technological landscape. Whilst the local authorities that engaged in this research did not articulate a definitive vision of what they felt their role should be, their commitment to delivering was clear, as was widespread concern that the market alone would not be able to meet the needs of all residents.

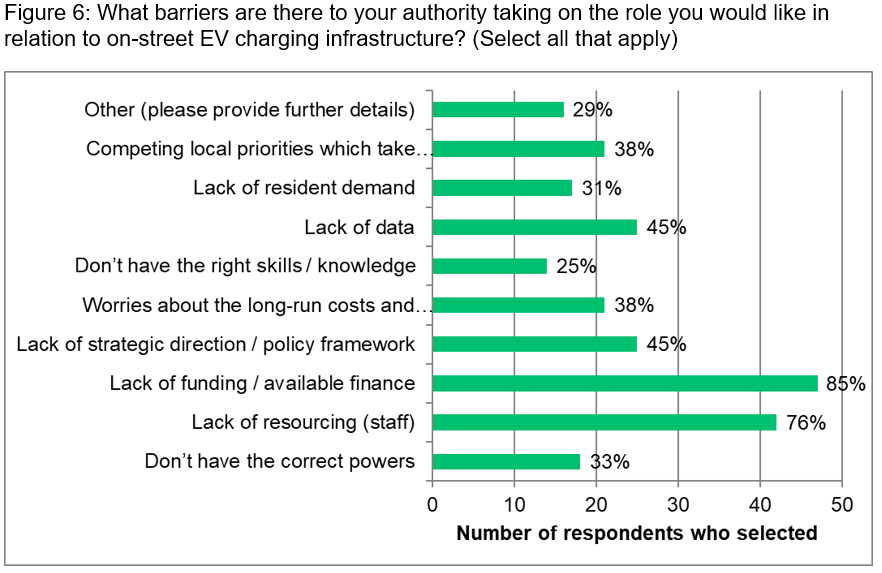

Key barriers to delivery that were raised by local authorities through the research were:

- lack of coherent strategic direction at a national level, including no articulation of the vision for the future and lack of clarity over the role authorities were expected to play in delivering EV charging infrastructure

- funding and resource constraints, with current funding structures too short term to allow strategic planning, and as they are based on competitive allocation do not focus on delivering where infrastructure is most needed

- lack of data to support decision making, including not having modelling of future demand

- difficulties engaging with DNOs on energy planning and grid connection, and as with other areas a lack of strategic approach to energy planning

- concerns over procurement approaches, with questions over whether authorities have the right commercial skills, and whether best practice is being shared across the sector, as each authority is developing new contracts and documents

- concerns over current market constraints and the extent to which this was driving commercial arrangements and decision making

- questions over the appropriate technology to invest in and apprehension about future technology obsolescence.

Whilst a significant majority of local authorities we engaged with were actively deploying or planning for EV charge infrastructure, a significant minority had decided that in the absence of a mandated requirement from government, and in light of uncertainty and constrained resources that this is not a priority for them at this time. If the government does not provide a clear mandate and accompany that with the necessary resources then some local authorities will choose to take different approaches.

Office for Zero Emission Vehicles (OZEV) and the role of local government

As part of an ongoing programme of engagement OZEV have recently been promoting discussion on five topic areas in relation to the role of local government:

- improving awareness and local leadership within local authorities

- improving capacity and capability within local authorities

- mechanisms for sharing knowledge and materials across local authorities

- exploring what role compelling local authorities (to provide on-street charging provision) should play

- working with local authorities on the transition of their own fleet vehicles.

Our findings in relation to these areas are as follows:

Improving awareness and local leadership within local authorities

There is a strong perception that national leadership could be stronger. In particular clarity at a national level on:

- the need to act

- the scale of necessary action

- issues around technology selection.

would go a significant distance to reducing local uncertainty, which in turn will strengthen the resolve of local leadership and increase delivery.

The majority of local authorities are already acting, whether or not they are able to access the government On Street Residential Chargepoint (ORCS) funding, seeing the clear synergies between EV charge infrastructure and their net zero ambitions or air quality responsibilities.

92% of local authorities we contacted felt that there is a role for local government across a range of activities including both planning and installation. The issues that need addressing are the specific roles for different types of authorities and the mechanism for resource allocation and the distribution of funding.

Improving capacity and capability within local authorities

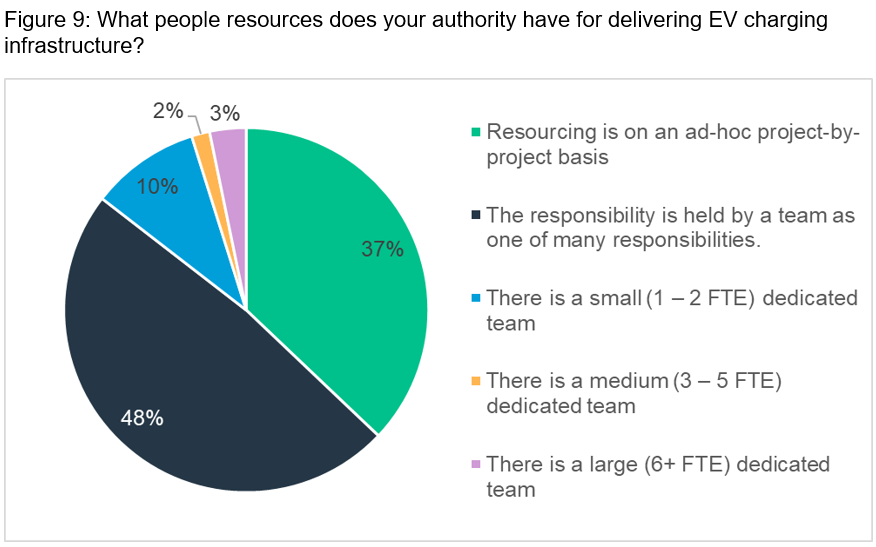

Both our survey and a survey undertaken by OZEV (distributed by the Energy Savings Trust) in May 2021 identified lack of funding and lack of resources as the biggest barriers to delivery. The resourcing available is very variable and not necessarily determined by the type of local authority.

Resource constraints are driving decision making in some local authorities including a decision not to install charge infrastructure and decisions to outsource all provision on a ‘nil cost’ basis, despite the other risks this can present.

In the main local authorities are keen to work collaboratively, and those that have done so have generally found it to be a positive experience. There is potential to explore using the sub-regional transport boards (STBs) as a regional umbrella – but this is not currently supported by the majority of local authorities that responded to the OZEV survey.

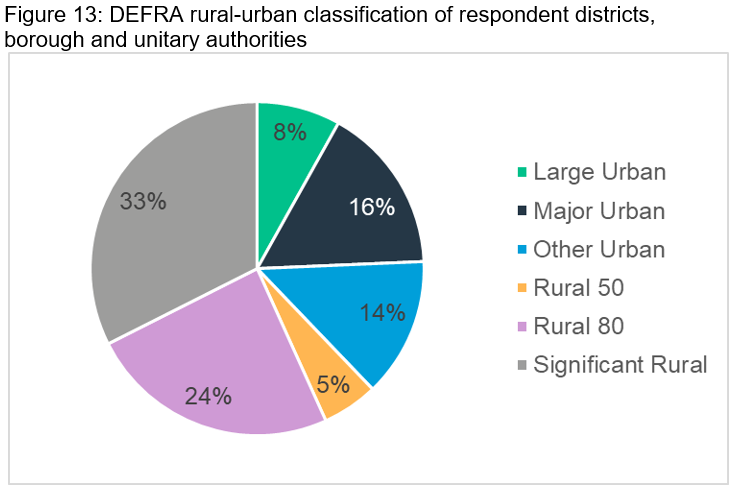

We are seeing the most delivery activity amongst housing authorities (unitary authorities, and districts and boroughs), but the STBs have their strongest relationships with the transport authorities (unitary authorities and counties). Therefore, it is possible that seeking to strengthen the relationships between the housing authorities and the STBs would be beneficial if OZEV continue to identify the STBs as integral to delivery.

If OZEV want to increase the pace of delivery, then additional resources (revenue and capital) need to be provided.

Mechanisms for sharing knowledge and materials across local authorities

There are already significant knowledge resources available to local authorities, for example through both the EST and Cenex websites and this is due to be supplemented shortly by the technical guidance OZEV are procuring through the Institute for Technology (IET). What has been missing is a mechanism to signpost from a single point the best resources for particular topics and applications and it is essential that the IET guidance is sufficiently comprehensive and readable to fulfil this role.

Local authorities are resource constrained and trying to operate in a market where demand currently outstrips supply. This is providing an environment where suppliers have the upper hand, and as a consequence there are risks to delivery of best value.

Local authorities need to be better armed with data and methodology to identify a clear list of priority locations. As the grid is not equal in all locations there is a need for sensible use of subsidies to avoid areas being left behind.

There needs to be more thought addressed to the decarbonisation of rural transport, particularly as public chargers in these locations may not be commercially attractive.

Identifying criteria for selecting the best technology for a particular location (which should include dumb gullies) in the forthcoming guidance should be a priority.

There are lots of areas that would benefit from knowledge sharing. The LGA and the STBs should be key players in this.

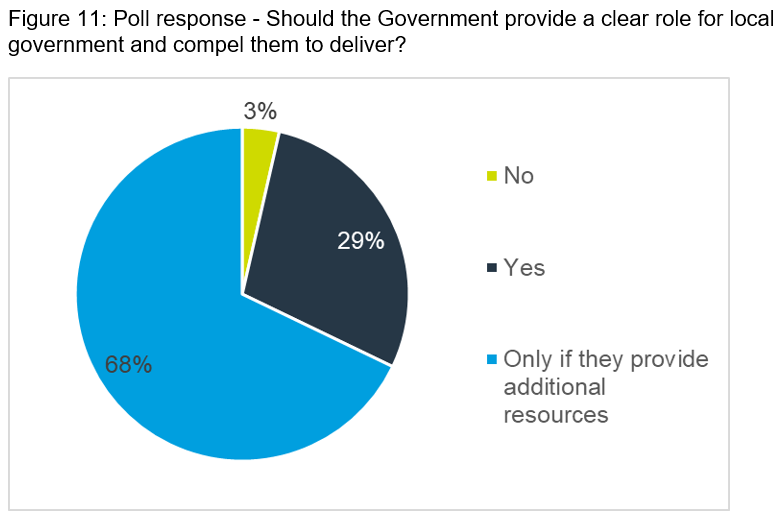

Exploring what role compelling local authorities (to provide on-street charging provision) should play

Local authorities are already resource constrained and the creation of any new burdens would need to be accompanied with new resources, both revenue and capital.

The imposition of requirements and the provision of funding might lead to faster deployment as they would provide some of the clarity that is currently lacking around the role of local authorities. However, targets would need to consider the nature of place, and be targeted at specific types of interventions, and would need to be acceptable to elected members.

Currently local authorities in some areas are experiencing difficulties in procuring EV charging equipment and contractors. The commercial market is expanding rapidly and there are currently resource constraints in the construction industry. If commercial operators are either not responding to tenders or are seeking to impose unreasonable contract conditions then now would not be the appropriate time to compel local authorities to act.

Working with local authorities on the transition of their own fleet vehicles

This question was out of scope for the work we have undertaken, however both Local Partnerships and the LGA are aware of significant activity already being undertaken in this area.

The free fleet reviews available to local authorities through EST are welcomed, although the delays currently being encountered to access the service were raised in the workshop sessions.

Recommendations

Based on the views of participants in the research and structured in line with the OZEV engagement topics there are ten asks for the LGA to address with Government on behalf of local authorities. These are:

- to clearly articulate the national roll out strategy for EV charging and the specific role to be played by councils. This should be supported by forecasts of requirement / targets for areas

- to provide national leadership on the issue of technology selection

- if OZEV want to increase the pace of delivery, revenue and capital resource will need to be provided

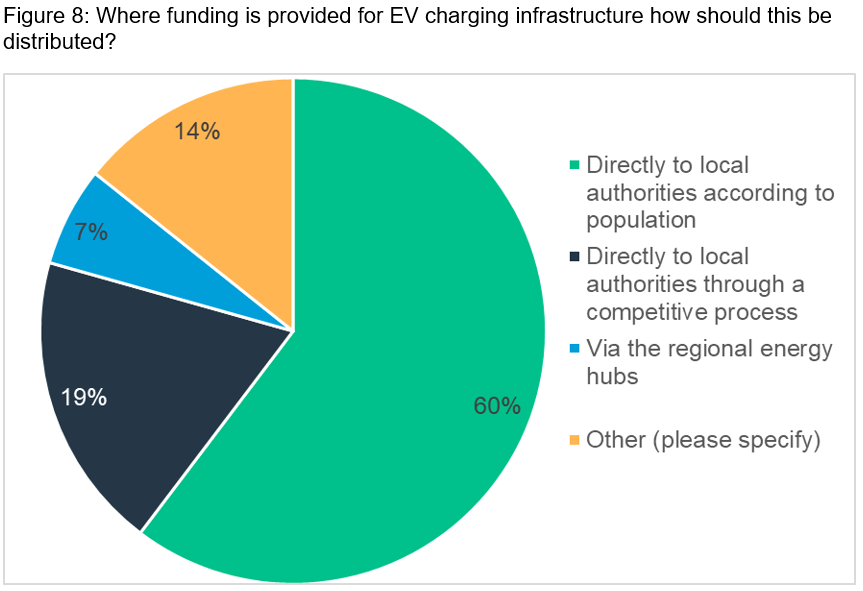

- to move away from the stop/start short term funding arrangement to a longer term 'outcome' based approach to funding, with the potential for this to be allocated based on predicted need, rather than competitively

- to strengthen relationships between STBs and housing and planning authorities, if OZEV see STBs as important to future delivery

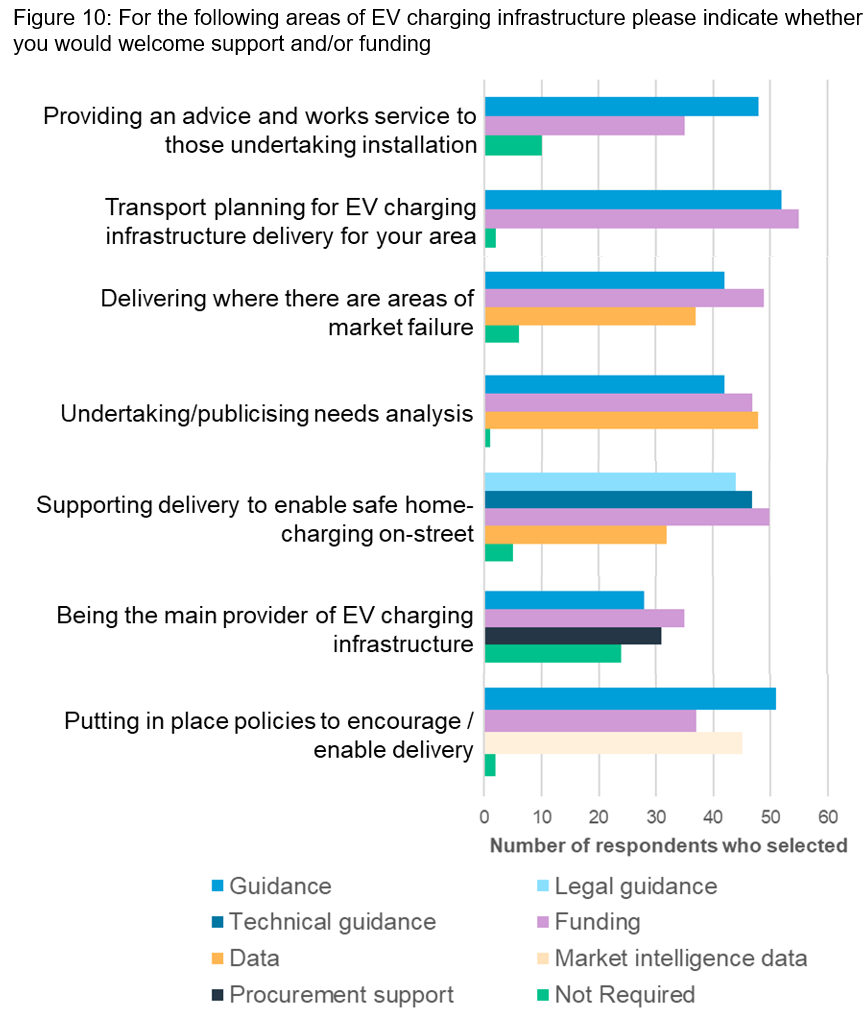

- to provide access to data in areas including market data, location modelling, delivery model choice, procurement and technology guidance

- in the forthcoming guidance, to identify criteria for selecting the best technology for a particular location (which should include dumb gullies)

- to make use of the LGA and STBs to support and enable knowledge sharing.

In addition, there were a number of areas identified where local authorities would welcome more support and/or guidance, including:

- procurement, including best practice and template documents

- use of data, including sharing of demand models and existing local authority data sources that can be used

- member education and training on issues relating to EV

- use of the pavement.