The text in this section draws heavily on an article by Ian de Prez, Solicitor Advocate for Suffolk Coastal District Council, in Local Government Lawyer magazine. We are grateful to Mr de Prez and Local Government Lawyer for their permission to reproduce the points from the article.

Passengers should be at the centre of a licensing authority’s taxi licensing policies and processes. As the Casey Review into Rotherham noted ‘The safety of the public should be the uppermost concern of any licensing and enforcement regime: when determining policy, setting standards and deciding how they will be enforced.’ There is no area where this is more important than in the application of the ‘fit and proper person’ test.

Licensing authority responsibilities

A licensing authority must not grant a taxi or PHV driver’s licence unless it is satisfied that the applicant is a fit and proper person to hold such a licence. This is very different to the Licensing Act 2003 or Gambling Act 2005, where the presumption is to permit a licence application.

To support considerations of whether a driver is ‘fit and proper’ the statutory standards suggest posing the following question: Without any prejudice, and based on the information before you, would you allow a person for whom you care, regardless of their condition, to travel alone in a vehicle driven by this person at any time of day or night? If, on the balance of probabilities, the answer to the question is ‘no’, the individual should not hold a licence.

A licensing authority is also entitled to suspend or revoke a taxi or PHV driver’s licence if there is evidence to suggest that the individual is not a fit and proper person, and specifically (see S60(1)(a)(b)(c), Local Government (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 1976) :

- if s/he has been convicted since the grant of the licence of an offence involving dishonesty, violence, or indecency

- for non-compliance with the licensing requirements of [the 1847 Act or the 1976 Act] and related legislation, or

- for any other reasonable cause.

Properly applying the ‘fit and proper’ person test is essential for ensuring a robust licensing scheme that protects safety and commands the confidence of the general public.

On receiving an application, councils should first check the applicant’s right to work. This ensures that applications are not heard where the applicant has no legal right to work in the UK and is a requirement of the Immigration Act 2016. In addition to checks of standard documents, councils may wish to use the Home Office’s free checking service for new or existing drivers. The service can be contacted at: [email protected].

The Finance Bill 2021 introduced the principle of ‘conditionality’ and from April 2022 councils will also be required to undertake new tax checks on licence renewal applications. This will affect taxi and PHVs drivers’ licences and PHV operators. HMRC will be publishing guidance for councils on how to undertake these checks as well as information for applicants and licensees outlining how they can demonstrate tax registration.

Once this is established, an inquiry into an applicant’s fitness to be licensed is likely to include enquiries into his health, local knowledge and understanding of the responsibilities of a licensed driver. However, character is usually investigated first.

Most councils have adopted a formal statement of policy about the relevance of convictions and how this assists in determining whether an applicant is fit and proper. While each application must be determined on its individual merits, the convictions policy should set out a recommended minimum period free of conviction for offences falling into broad categories as a guideline for licensing committees.

The reason a person’s past criminal conduct is taken into consideration is that it can indicate what is likely to happen in the future if a licence is granted.

However, councils should not focus solely on an applicant’s convictions as an indication of their character. For instance, failure to comply with regulatory requirements may not itself be criminal but may demonstrate a concerning tendency to disregard licence conditions. Factors such as anti-social behaviour, solvency and sobriety may also be relevant.

Convictions policy

It is important to set out how your sub-committee will view convictions, spent or otherwise, and ideally include it as part of your consolidated taxi licensing policy. Decisions on licensing drivers are exempt from the provisions of the Rehabilitation of Offenders Act and so historic convictions that might otherwise be considered as spent or expired can be taken into consideration. The Institute of Licensing has published guidance in relation to protected convictions and cautions and the licensing process to support councils.

As set out above, licensing authorities should set out their approach in a convictions policy which should be regularly reviewed and updated as appropriate. The IoL, in partnership LGA, Lawyers in Local Government (LLG) and NALEO, has developed guidance on determining suitability, which is a useful tool for local authorities in developing their own policies. The DfT’s statutory standards includes an annex on Assessment of Previous Convictions which is based on this suitability guidance.

In particular, the LGA encourages councils to take a strong stance on indecency offences, such as those relating to sexual assault or rape. While each case must be considered on

its own merits, the default position should be that if an applicant has a previous conviction for a sexual offence, a licence will not be issued. Members should be aware of the wide range of criminal offences identified in the Sexual Offences Act 2003 that are very strong indicators of risk if an offender were enabled to be alone in a licensed vehicle with a young person or vulnerable adult.

In addition to indecency offences, Parliament also singled out offences of violence and dishonesty as being of particular concern and relevance when issuing licences, and your policy should weight these offences accordingly. Again, while each case must be considered on its own merits, the IoL guidance sets out a default position whereby an applicant with a conviction for a violent offence or driving offence involving a loss of life will be refused a licence.

The convictions policy should set out expectations for how the licensing authority will remain updated about relevant convictions after the point at which a licence has been granted. The Disclosure and Barring Service (DBS) update service, which costs an applicant £13 a year, can help to ensure that licensing authorities receive relevant information as quickly as possible. The LGA and DfT statutory standards suggests that all licensing authorities consider making it mandatory for drivers to register for the update service and nominate the licensing authority to be able to check the status of the certificate at any time. Licensees should be able to provide evidence of continuous registration and nomination throughout the duration of their licence.

If licensees are obliged under their licence to inform the local authority of their arrest or conviction and they fail to do so (or where they fail to notify the police that they hold a licence), this should be viewed particularly seriously as it prevents the local authority from taking that information into account when protecting public safety. This is also a breach of condition and can be actioned by the authority on that basis. Whilst the law does not allow conditions to be added to a hackney carriage driver licence, many councils only issue ‘dual’ private hire / hackney carriage driver licences in order to address this point. Alternatively, licensing authorities may wish to attach a condition to hackney carriage vehicle licences for the proprietor to notify the licensing authority as soon as they become aware that a driver of the vehicle is arrested, charged, cautioned or convicted of an offence.

Use of soft intelligence

It is important to remember that your decisions need not, and should not, be based solely on convictions. Licensing committees can consider soft intelligence provided by the police and other partners, as well as of the applicant’s responses in the committee hearing. Crucially, the evidential threshold for licensing committees is not the ‘beyond reasonable doubt’ standard which is the criminal standard of proof for criminal trials.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that some authorities have been reluctant to attach much weight to non-conviction information, and in some instances have even doubted the propriety of reporting it to members. However, there is no doubt that this information can and should be considered and may sometimes be the sole basis for a refusal, a suspension or revocation.

When dealing with allegations rather than convictions and cautions, a decision maker must not start with any assumptions about them. Allegations will have been disclosed because they

reasonably might be true, not because they definitely are true. It is good practice for the decision makers, with the help of their legal adviser, to go through the contents of an enhanced disclosure certificate with an applicant/driver and see what they say about it. If, as sometimes happens in practice, admissions are made about the facts, that provides a firm basis for a decision.

It will not be possible to give a comprehensive list of points that will be considered as part of the fit and proper person test, but each council should set out in writing, preferably as part of its licensing statement, an outline of how the council intends to approach these decisions and what factors will carry the most weight.

National Register of Taxi/PHV Licence Revocations, Refusals and Suspensions (NR3S)

The licensing history of an applicant is an important factor to consider, and it will always be relevant for an authority to consider a previous refusal or revocation, and the reasons for that decision. Whilst every application must always be considered on its own merits, a previous decision may in many cases warrant significant weight to be given to it – assuming a licensing authority knows about it.

The LGA launched the National Register of Taxi Licence Revocations and Refusals (NR3) in 2018. NR3 provides a mechanism for licensing authorities to record details of where a taxi or PHV drivers’ licence has been refused or revoked, and allows licensing authorities to check new applicants against the register. The simple objective of NR3 is to ensure that authorities can take properly informed decisions on whether an applicant is fit and proper, in the knowledge that another authority has previously reached a negative view on the same applicant.

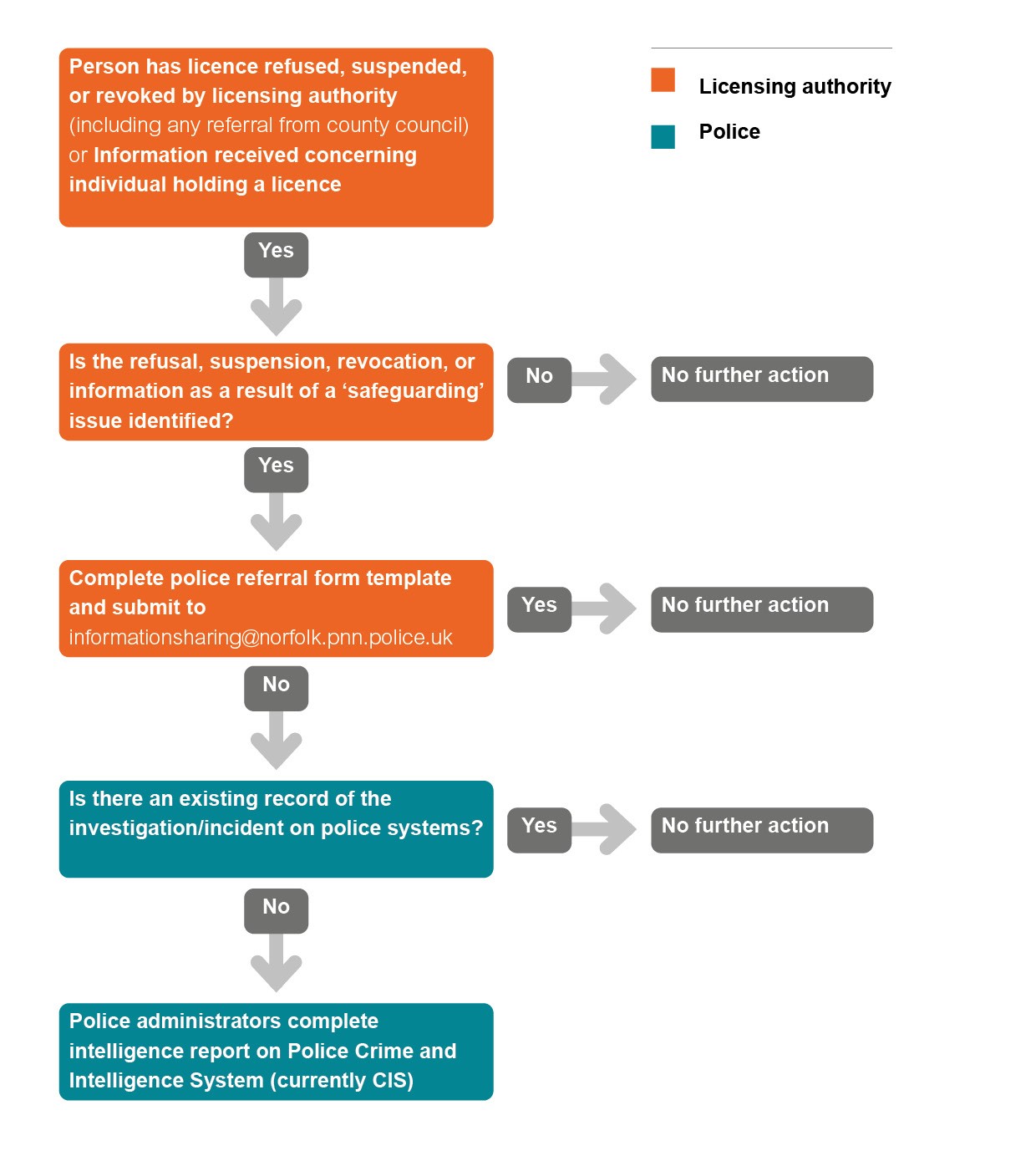

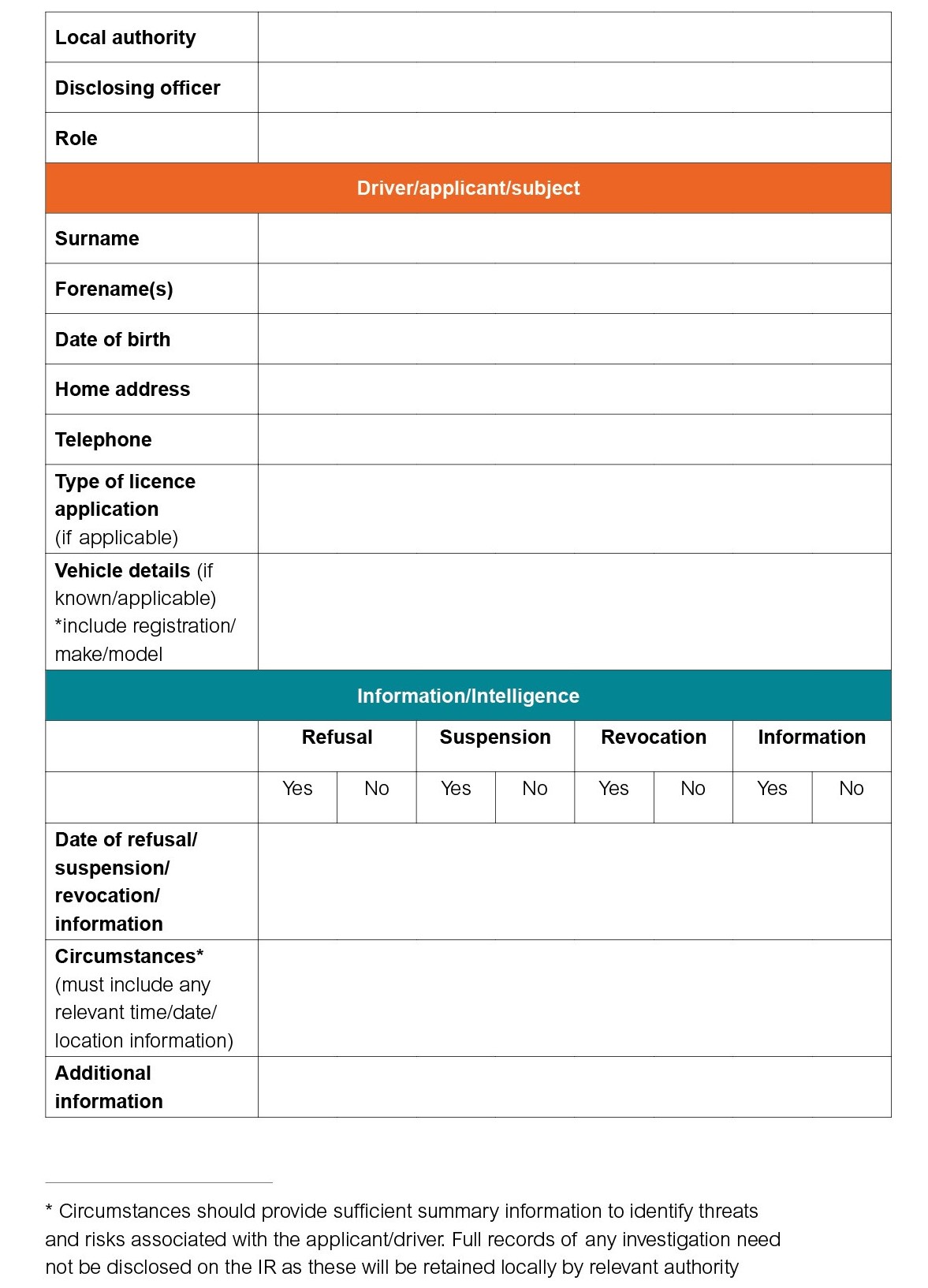

The Taxi and Private Hire Vehicle (Safeguarding and Road Safety) Act 2022 requires all licensing authorities to record information regarding drivers’ adverse licensing histories (refusals, suspensions or revocations of licences) on the NR3S database (which was rebranded, following the passage of the Act, to reflect that the database now includes suspensions). The Act also requires licensing authorities to search the NR3S for any entry relating to an applicant before reaching a decision on whether or not to grant a taxi/PHV licence. If there is a relevant entry on the applicant, the authority must contact the recording authority to request the relevant information. The decision-making licensing authority must then have regard to the information provided when making their decision.

Queries about the NR3S database should be directed to [email protected].

PHV operator responsibilities

Taxi and PHV licensing is not an area where there is much scope for self-regulation, but PHV operators do have a key role in ensuring that their drivers are fit and proper persons, that the vehicles they use are adequate and insured, that their staff handle customer information correctly, and that everyone is properly trained in their roles including awareness of child sexual exploitation (CSE) and disability equality.

As part of a ‘fit and proper’ assessment the statutory standards recommend that licensing authorities request a basic disclosure from the DBS for PHV operators as part of the application and then on an annual basis. Authorities should consider whether an applicant or licence holder meets the ‘fit and proper’ threshold if they have a conviction for an offence included in the IoL’s guidance or annex to the statutory standards.

Your policy should therefore cover the responsibility of PHV operators for ensuring that their drivers are fit and proper persons. As part of the process of granting and monitoring an operator licence, you may wish to require operators to demonstrate what steps they are taking to ensure that their drivers are fit and proper persons, as well as appropriately trained.

This responsibility is even more important now that the Deregulation Act has enabled operators to sub-contract bookings to other providers. There are existing obligations on operators who seek to pass on a booking and the first operator will always retain overall responsibility for its fulfilment. However, there is scope for councils to enhance this responsibility by placing conditions on an operator’s licence to require them to set out how they will handle sub- contracting and ensure consumer protection.

It is also appropriate to remind operators that they have responsibilities towards their drivers and should ensure that they are not working excessive hours. A case in Mansfield of a driver falling asleep at the wheel and causing a fatality was investigated by the coroner, who recommended greater attention was given to ensuring drivers were not unduly fatigued. This is most effectively done by the operator, who will have more regular contact with the driver and should be reminding them of the serious consequences that can result if they drive for excessive hours.

These are areas that have not yet been tested through the courts and offers a fertile ground for those innovative councils who wish to make full use of their powers to protect their communities. We encourage councils to explore this, and to share their new practice with the LGA and other licensing authorities.

Changes in technology mean that there are newly emerging operator models, which can require scrutiny to ensure that they comply with the law as it stands. Functions and processes that are well established among non-digital operators may need to be questioned and traced when considering a proposal to operate online. A checklist of questions to ask is included at the end of this handbook, although the list is not exhaustive.

Monitoring complaints

All councils should have a robust system for recording complaints, including analysing trends across the whole system as well as complaints against individual drivers. Complaints about drivers should be taken seriously and drivers with a number of complaints made against them should be contacted by the council and concerns raised with the driver and operator (if

appropriate). Further action must be determined by the council, which could include no further action, the offer of training, a formal review of the licence or formal enforcement action.

The licensing committee should review the complaints procedure and records regularly, and always before a review of the licensing policy. It is expected that councils will carry out ‘mystery shopping’ and test purchasing checks on licensed vehicles. The committee should have oversight of this to ensure that the council is properly carrying out its enforcement responsibilities.

Penalty points enforcement system: Rother District Council

When taxi and PHV drivers contravene conditions of their licence the only sanctions available to members of taxi licensing committees is that of revocation or suspension. For minor infringements, such as not displaying a name badge at all times, revocation or suspension can be too harsh a punishment. Drivers who make an error in judgement on any given day, with a previous unblemished career, may face all or nothing decisions by councillors if they are reported to committee following a complaint from a member of the public.

Also, once drivers are licensed there is limited information available to continually assess whether they are fit and proper persons, and as such for members to have a clear view of their past conduct when drivers are called to committee for hearings.

In light of this Rother District Council decided to develop a ‘penalty points enforcement scheme’, where drivers can carry a fixed number of points for minor matters of misconduct that would allow the driver to continue driving until such time as they either reached the level set by members, at which point there would be a hearing, or if officers decided that the nature of the complaint against a driver was too serious to deal with under the scheme.

Rother found that on the whole the trade agreed that the process led to improvements in behaviour, especially by those drivers who tend not to take their role as licensed drivers too seriously. The trade appreciated that the scheme is transparent and clear, and removes any ambiguity about whether officers or members felt that a matter was serious, or when the driver thought it was very minor.

The penalty points enforcement scheme gives councillors a more influential role in the licensing process, and it allows drivers to understand that members make the decisions on fitness and propriety and not officers. However, it is worth noting that the accumulation of points cannot automatically lead to a sanction and that the ‘fitness’ or otherwise of a licensee has to be dealt with separately and in its own way.

Many other councils have introduced similar schemes and there has been a noticeable improvement in both standards of behaviour and standards of compliance. Councils should have regard to case law that has established parameters for these schemes, including a judgement in Singh v Cardiff that the scheme must not fetter the discretion of the decision maker.

Scrutiny

Public scrutiny is an essential part of ensuring that government remains effective and accountable, and this is especially true of quasi-judicial systems like taxi and PHV licensing. Scrutiny ensures that executives and committees are held accountable for their decisions, that their decision-making process is clear and accessible to the public and that there are opportunities for the public and their representatives to influence and improve public policy.

There are a number of aspects of taxi and PHV licensing that are suitable for a scrutiny investigation, ranging from a review of the policy and framework, including how it contributes to a wider transport policy, its success in delivering accessible transport for disabled users, or the handling of complaints; to more specialist subjects such as the setting of fees, provision of taxi ranks, or the age and maintenance of the fleet.

The Centre for Public Scrutiny provides guidance on how to hold effective scrutiny and has a number of case studies from councils that have already held scrutiny enquiries into their taxi and PHV licensing systems.