The key components of the improvement and assurance framework for local government are set out in the following categories, shown diagrammatically through the links below:

Some of these components are required by legislation (e.g. the requirement for the s151 officer to report to full council if they consider that a decision will incur unlawful expenditure). Many include a mixture of legislative requirements and best practice (e.g. ensuring appropriate governance and reviews of joint ventures and local authority trading companies). Others reflect practice which is not set down in statute but is necessary in a well-run authority. A significant proportion reflect content from the best value standards and/or reports relating to ‘failed’ councils which identify where key activities were absent or poorly performed.

More information about each component, with links to relevant guidance and improvement support, appears below. Engagement with sector support is itself a key component of the framework- whether from other authorities, regional, national and/or professional bodies - for benchmarking, sharing good practice and seeking assurance and support for improvement. All authorities – including those seeking to move from good to great – can benefit from looking outwards to learn from practice elsewhere.

The LGA’s regional teams can advise on a range of support for local authorities which will help understanding and implementation of the assurance activities shown below. This includes bespoke support and mentoring in addition to:

In addition to considering what the key components are, read on to consider how they are implemented, with information about key principles and what good looks like.

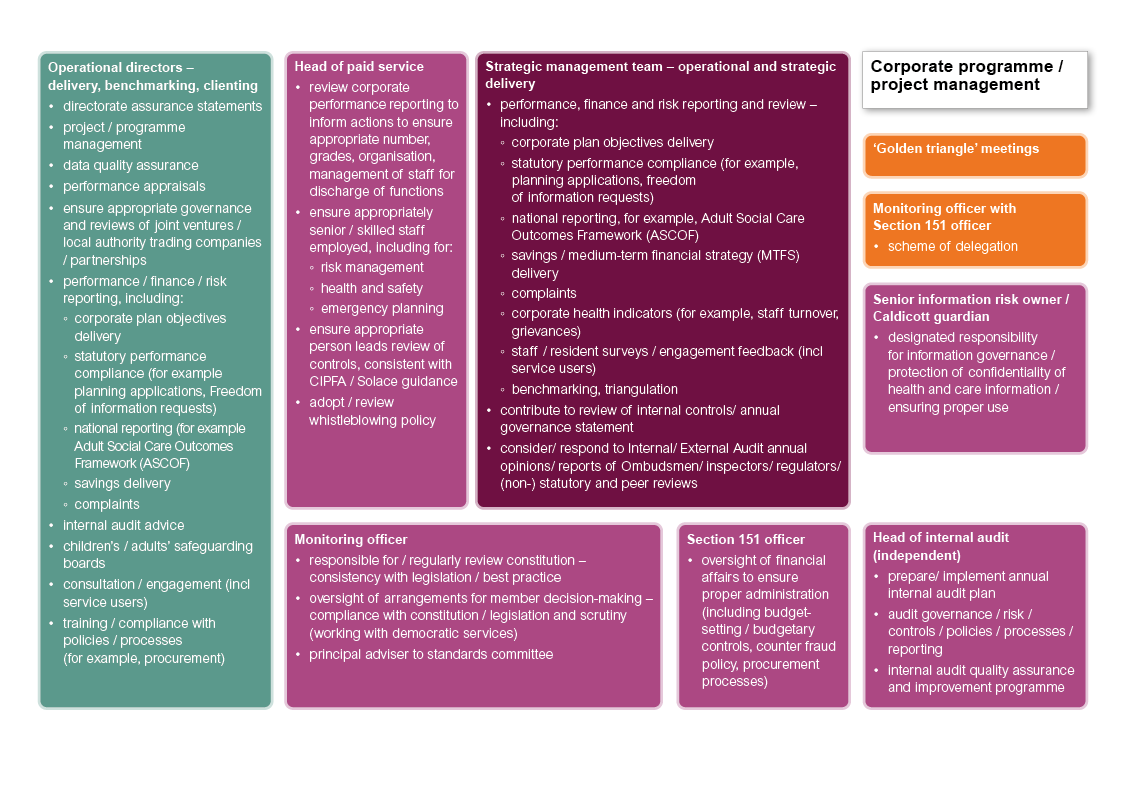

Actions to contribute to assurance of local authorities by officers (not normally in public)

Open a larger version of this diagram

- Operational directors ensure that:

- directorate assurance statements to inform the annual governance statement are comprehensive and accurate, informed by an assessment of compliance with all relevant policies and procedures;

- project and programme management complies with corporate requirements and good practice;

- data used to inform decision-making and performance monitoring is of high quality. Effective performance management, using good quality data, is a necessary contribution, but is not the only source of assurance. Services where poor performance may be less visible (such as social care) require additional, and different performance management;

- performance appraisals are conducted consistently, with individual objectives linked to corporate objectives; capability and disciplinary procedures are utilised consistently and as appropriate;

- appropriate governance is in place for any partnerships, joint ventures and local authority trading companies and that it is reviewed regularly (including ensuring clarity of shareholder roles, avoiding conflicts of interest and consideration of independent data on performance);

- there is appropriate oversight of reporting on performance, finance and risk, including:

- delivery of corporate plan objectives

- compliance with statutory requirements (e.g. timescales for determination of planning applications, response to FOIs)

- national outcomes frameworks (e.g. ASCOF)

- delivery of budget savings

- responses to and learning from complaints;

- actions in response to internal audit recommendations are implemented to agreed timescales;

- effective consultation and engagement with service users and wider communities informs service design, planning and delivery. This is fundamental to accountability and requires consideration of any actions or support required to enable communities to engage with the authority;

- all necessary training is delivered to relevant members and officers to enable compliance with policies, procedures and strategies (including HR, standards, procurement and risk management). For senior member and officer roles, this should include space to reflect on practice, for example through mentoring.

- Corporate programme/ project management reflects good practice, with capacity and capability commensurate with the scale, complexity and risk of the authority’s major programmes.

- The strategic management team effectively oversees operational and strategic delivery, including:

- reporting and review of performance, finance and risk, including:

- delivery of corporate plan objectives

- compliance with statutory requirements (e.g. timescales for determination of planning applications, response to FOIs)

- national outcomes frameworks (e.g. ASCOF)

- delivery of budget savings and medium term financial strategy

- responses to and learning from complaints

- corporate health indicators (e.g. staff turnover, grievances)

- staff/ resident surveys and feedback from service user and community engagement

- benchmarking with relevant organisations

- triangulation of all sources of data on performance;

- contributing to the review of the effectiveness of the authority’s governance arrangements to inform the annual governance statement;

- considering and responding to annual reports by internal and external audit, ombudsmen, inspectors, regulators and peer reviews, and statutory/ non-statutory reviews.

In addition to considering all of the above individually, it is essential that the strategic management team consider the cumulative impact where limited or no assurance is possible in relation to more than one issue or service. A trend of, for example, increasing complaints, whistleblowing and staff turnover may be an indicator of more systemic failings.

- The head of paid service:

- reviews corporate performance reporting to inform their actions to ensure the appropriate number, grades, organisation and management of staff for the discharge of the authority’s functions;

- ensures appropriately senior and skilled staff are employed, including for:

- risk management

- health and safety

- emergency planning and business continuity;

and that these arrangements are appropriately managed and coordinated;

- ensures that an appropriate person leads the review of the effectiveness of the authority’s governance arrangements to inform the annual governance statement;

- ensures adoption, effectiveness and regular review of the authority’s whistleblowing policy.

Top tips for chief executives in ensuring good governance and assurance.

- The monitoring officer:

- regularly reviews the constitution to ensure that it reflects both legislation and good practice (working with Democratic Services);

- oversees arrangements for member decision-making, ensuring their compliance with the constitution and legislation

- acts as principal adviser to the Standards Committee (the LGA has commissioned guidance and training materials to support monitoring officers in this role).

- The chief finance officer is responsible for ensuring proper administration of the authority’s financial affairs (including budget-setting, budgetary controls, procurement practices and the authority’s counter-fraud policy).

- The head of paid service, monitoring officer and chief finance officer act together as the ‘Golden Triangle’ to ensure and support good governance in the authority.

- The monitoring officer works with the chief finance officer to ensure that the authority’s scheme of delegation is regularly reviewed, appropriately comprehensive, current, and with member-level decision-making and transparency proportionate to the scale of the authority’s activity and risks.

- The Senior Information Risk Owner has responsibility for information governance and managing information security risks. In upper tier and unitary authorities, the Caldicott Guardian ensures that the confidentiality of people’s health and care information is protected and that it is used correctly.

- The head of internal audit provides independent assurance by:

- preparing the annual internal audit plan, informed by risk in the authority, and implementing that plan;

- auditing the authority’s governance, risk management, controls, policies, procedures and reporting;

- developing and implementing the internal audit quality assurance and improvement programme, including external assessment against the Public Sector Internal Audit Standards.

Working with auditors

Actions to contribute to assurance of local authorities by members and officers working together (sometimes but not always in public)

- Officers provide professional advice which informs members’ decisions. It is essential that this advice includes all relevant information (including consideration of risk and options analysis), is current and presented in a way that is comprehensible to the decision-makers.

Where this information relates to a ‘key decision’, such information might appear in background papers which would normally be published. Authorities need systems in place to recognise where this applies and to ensure that papers are consistent and comprehensive.

Members and the public can be supported to understand the implications of the annual budget if the ‘s.25 statement’ by the chief finance officer on the council’s financial sustainability is clearly worded in non-technical language and is prominent as a separate report on the Cabinet/ Policy and Resources Committee and full council agendas.

Where a decision is required on very technical matters (for example on treasury management or certain kinds of commercial decisions), the council may need to engage industry specialists to inform decision-making (including the preparation of technical assessments).

Assurance is not a one-off activity: the advice or business case on which a decision was based may change over time. Officers have a responsibility to bring such changes, where material, to the attention of decision-makers. Where no assurance is possible due to changed circumstances, this may require consideration of additional mitigations or even the reversal of the decision.

Guidance on taking a structured and robust approach to considering commercial activity

- Each portfolio holder or policy committee chair meets regularly with directors relevant to their remit to review performance, finance and risk, consider activities required where assurance is not gained, and ensure appropriate formal reporting to members;

- The community safety partnership has oversight of the development and implementation of relevant cross-organisation strategies;

- Other boards and partnerships, such as Growth Boards or Joint Committees, are constituted to oversee activities which can only be achieved by the local authority working in partnership with others. Clear governance arrangements are essential to enable assurance of the partnership’s activity and accountability for delivery.

Less work has been undertaken to date to understand good practice in assurance of partnership activities (formal and informal) where there is shared accountability for delivery: the LGA will commission work to support a greater understanding of this topic in 2024/5.

- The authority may commission peer-led challenges for individual service areas and/or at corporate level, from the LGA (e.g. corporate peer challenge), professional bodies (eg CIPFA financial resilience advisory reports) and regional bodies. The corporate peer challenge (CPC) considers the effectiveness of the authority’s political and managerial leadership, as well as its prioritisation, culture, governance, financial management and capacity to improve: authorities are expected to publish the report and action plan and have a follow-up visit to review progress. The preparation of an honest self-assessment ahead of a CPC is an important part of the process.

- A Council Improvement Board or Independent Assurance Panel (e.g. Wirral) may provide additional focus to and assurance of the authority’s improvement activity, which may be targeted on prevention as opposed to recovery from failure.

The LGA will produce a version of this framework for elected members explaining their roles in contributing to the assurance of the authority.

Actions to contribute to assurance of local authorities by members and officers in public

- The Executive / Policy and Resources Committee reviews performance, finance and risk reporting at a strategic level, including:

- delivery of corporate plan objectives;

- compliance with statutory requirements (e.g. timescales for determination of planning applications, response to FOIs)

- national outcomes frameworks (e.g. ASCOF)

- delivery of the medium term financial strategy

- corporate health indicators (eg staff turnover, grievances).

Reporting should be regular: good practice would be at least quarterly;

- In authorities with the executive governance model and those with the committee system which choose to appoint them, overview and scrutiny committee(s):

- review performance/ finance/ risk reporting

- undertake pre-decision and/or budget scrutiny

- call-in executive decisions

- undertake scrutiny reviews in order to support policy development or consider and review strategic options.

The work of scrutiny is supported by the statutory scrutiny officer.

When reviewing finance and risk issues, scrutiny will need to have regard both to the work of the audit committee but also to the executive’s own role in oversight and assurance.

There is statutory guidance which sets out how effective overview and scrutiny should be conducted, and support and further guidance is available from the Centre for Governance and Scrutiny. For devolved areas, a scrutiny protocol provides further detail.

- The Appointments Committee recommends to full council the appointment of appropriately qualified statutory officers;

- The Audit Committee:

- monitors and reviews the effectiveness of the authority’s internal controls, risk management and financial reporting holds internal and external audit to account;

- approves the internal audit plan, ensuring that it is informed by the strategic risks facing the authority. It oversees the plan’s implementation and ensures compliance with the Public Sector Internal Audit Standards (set by CIPFA, who add interpretations for the UK public sector to international internal audit standards);

- reviews internal and external audit reports and opinions and oversees management responses;

- assesses its own practice (an annual external review is recommended)

- may include lay members to provide additional expertise.

CIPFA provides more detailed guidance, including terms of reference for Audit Committees.

The LGA provides a range of support for audit committees:

The Centre for Governance and Scrutiny has produced guidance on the respective roles of audit and scrutiny committees.

- The committee with delegated responsibility for governance:

- reviews the draft annual governance statement

- oversees regular reviews of the constitution.

- The Standards Committee:

In many authorities the committee is also responsible for overseeing the development and implementation of programmes of member training, ensuring their appropriateness and take-up by members. If this is not within the remit of Standards Committee, the authority will need to ensure that another member-level body has that remit.

The role of Standards Committee as part of the governance framework is distinct and should be separate from that of the Audit Committee which oversees the effectiveness of that framework.

- The following officers have a statutory duty to report to full council:

- The head of paid service, on arrangements for discharge of the authority’s functions (s.4 of the Local Government and Housing Act 1989)

- The chief finance officer (s.151 officer in councils and s.73 officer in combined authorities):

- on the robustness of the estimates for expenditure and adequacy of the proposed financial reserves (s.25 Local Government Act 2003)

- if there is or is likely to be unlawful expenditure or an unbalanced budget (s.114 of the Local Government Finance Act 1988)

- The monitoring officer on matters they believe to be illegal or amount to maladministration (s.5 of the Local Government and Housing Act 1989)

Before issuing a report, the chief finance officer or monitoring officer must first consult (as far as is practicable) with the head of paid service and each other.

- Full Council is the body charged with the governance of the council and while it may delegate some responsibilities it remains accountable and therefore should seek assurance. It does this by:

- Considering the s.25 statement of the chief finance officer of the robustness of estimates and adequacy of reserves before approving the budget;

- Reviewing (at least) an annual report from each of the chairs of the Overview and Scrutiny Committee (where relevant), Audit and Standards Committees and holding them to account;

- Appointing appropriately qualified statutory officers.

Consideration of the external auditor’s annual report would also represent good practice.

Actions to contribute to assurance of local authorities by other bodies (not usually in public)

- Grant funding bodies place many and varied reporting requirements in relation to their programmes, including where the local authority is the accountable body for other agencies and wider partnerships;

- Regional networks may undertake benchmarking and maintain an overview of performance, providing constructive challenge and in some cases improvement support (e.g. London’s Self Improvement Board)

- Officials from the Department of Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC) undertake early engagement with local authorities where they become aware of qualitative or quantitative indicators of potential failure, to understand their organisational challenges in relation to governance, finance and service delivery and to gain assurance of how they are being managed. Best Value Standards and Intervention: a statutory guide for best value authorities (section 5)

- The Office for Local Government (Oflog) will conduct ‘early warning conversations’: discussions with local authorities identified as potentially at risk. Where the initial conversation is deemed to provide insufficient assurance, the authority will be visited by a team of reviewers who will then set out their findings and recommendations in a published report.

- Government departments make ad hoc requests for information and assurance where they have queries or concerns relating to local authority performance relevant to their remit.

- Political parties have their own disciplinary processes in relation to the conduct of members of their parties – including elected members:

The parties also have their own approaches to engagement with authorities where they are the largest party and where significant performance issues have been identified.

- Local -or external – audit undertakes assurance activity throughout the year and acts as a critical friend.

- Professional bodies have varying roles in relation to standard setting, the specification and awarding of qualifications, capability and disciplinary procedures and guidance and tools to support decision making. In relation to corporate service areas, the following bodies have key roles:

| Finance |

The chief finance officer in England must be a member of one of the following bodies:

|

| Internal Audit |

|

| Legal services |

There is no requirement for a monitoring officer to be legally qualified. For those that are, the following bodies are relevant:

|

- The LGA maintains an overview of the performance of the sector.

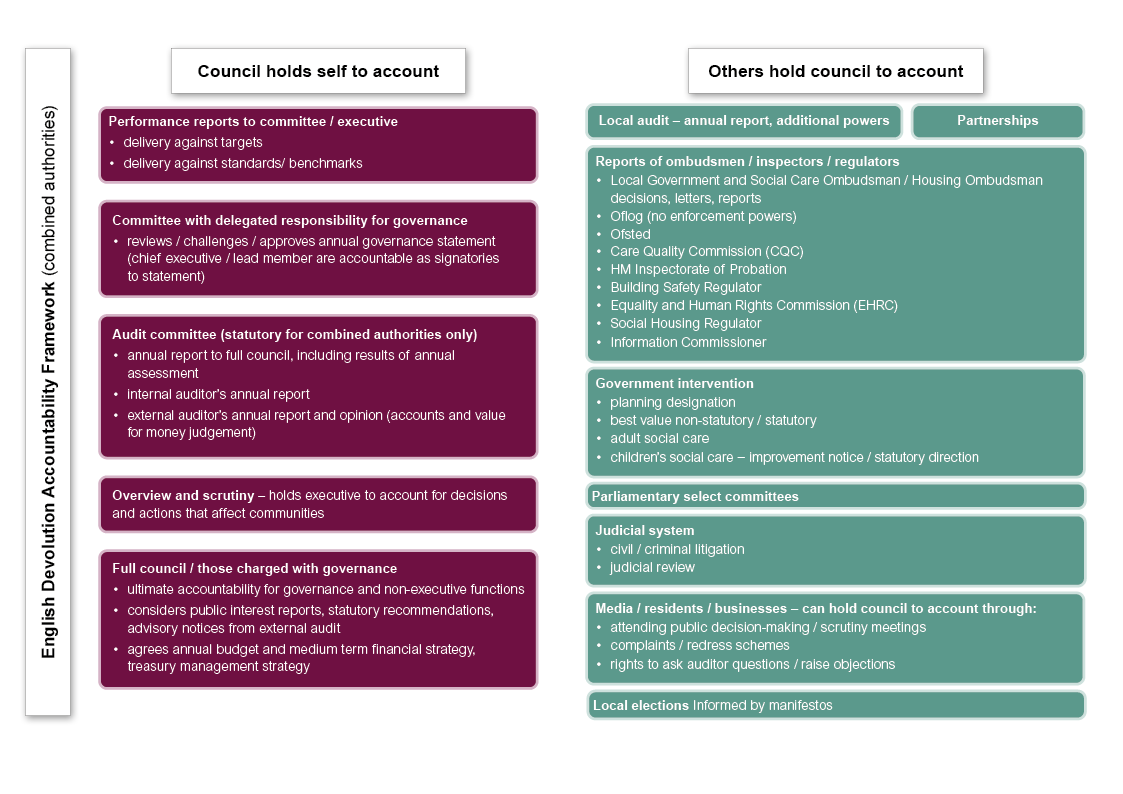

How does the authority hold itself to account?

Open a larger version of this diagram

- The English Devolution Accountability Framework sets out how devolved areas are scrutinised and held to account through local scrutiny, by the public and by government.

Good governance for combined authorities

- The Executive/ Policy and Resources Committee holds itself to account for delivery against performance targets, standards and benchmarks;

- In authorities with the executive governance model, overview and scrutiny committees hold the Executive to account for the decisions and actions that affect local communities;

- The Audit Committee:

- holds management to account in relation to the opinions of internal and external audit and for the implementation of their recommendations

- is held to account by Full Council through an annual report, which should include reference to a self-assessment of its own performance;

- The committee with delegated responsibility for governance reviews, challenges and approves the annual governance statement and holds management (via the chief executive and lead member as signatories) to account for implementation of improvement actions identified;

- The Full Council:

- is ultimately accountable for the council’s governance and other non-executive functions

- considers and must ensure appropriate responses to public interest reports, statutory recommendations and advisory notices from external audit

- agrees the annual budget, medium term financial strategy and treasury management strategy.

How do others hold the authority to account?

- Ombudsmen, inspectors, regulators and others issue reports which require the authority to take action. While most of these (and the more formal interventions which follow) relate to specific services, a failure leading to an adverse judgement by one of these bodies is a probable indicator of wider failings in assurance:

- Building Safety Regulator*

- Care Quality Commission*

- Equality and Human Rights Commission*

- HMI Probation

- Housing Ombudsman*

- Information Commissioner*

- Local Government and Social Care Ombudsman

- Ofsted*

- Regulator of Social Housing

*Body with powers to take or trigger enforcement action;

Where there are services with a greater degree of regulation – often those with the largest budgets – this may skew assurance activity and attention. It is important for authorities – and particularly the chief executive – to understand the scale and nature of assurance (both internal and external) of all higher-risk services and to put additional measures in place where necessary.

There is guidance for members and chief executives to help them understand their roles in relation to the assurance of children’s services:

- Chief executives 'must know' for children’s services

- Must know: The role of a council leader in improving outcomes for children

- 'Must knows' for children's services portfolio holders

- Government departments formally intervene by issuing directions (statutory interventions) or requests (non-statutory interventions):

- A parliamentary select committee may require a local authority to appear in front of it in relation to concerns about its performance;

- The judicial system may hold a local authority to account, whether through criminal or civil litigation, or judicial review;

- Local residents and business and the media can hold their local authority to account by:

- attending public decision-making and scrutiny meetings, asking questions where permitted by the constitution

- making use of complaints or redress schemes

- invoking rights to ask the auditor questions and/or raise objections;

- Local residents hold elected members to account at local elections.