Local government has received hundreds of grants in recent years

English local government received at least 448 unique grants from central government between 2015/16 to 2018/19. In any given year, they receive roughly 250 grants.

Councils receive more grants now than in the past

Direct comparisons are difficult due to the comprehensive nature of this research. However, previous research carried out by the National Audit Office in 2014 suggests that approximately 61 main grants were paid to local authorities in 2013/14.

The total amount of grant funding going to local government is decreasing

Councils’ grant funding from central government has fallen from £83.1 billion in 2015/16 to £69.9 billion in 2018/19 – a decrease of 15.8 per cent over four years. This includes steep decreases in both revenue and capital funding.

Based on budget figures published by the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG) in 2019/20, funding for councils will continue to fall.

The most significant grants to councils are decreasing

Most of the funding for councils comes through a few large grants, including housing benefit funding, the revenue support grant, and the public health grant.

However, the size of these grants has decreased over time.

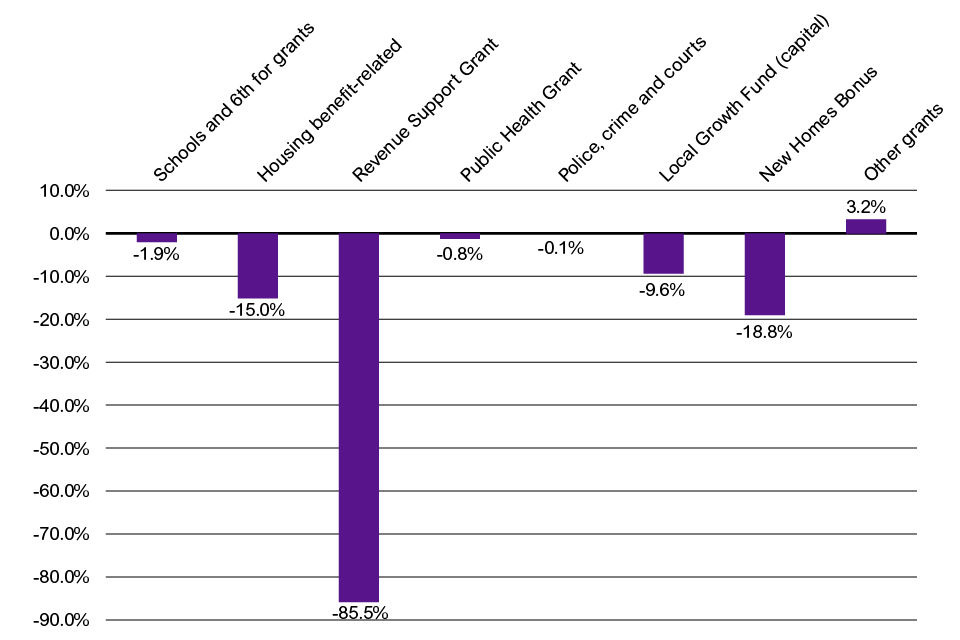

Figure 1: Change in funding between 2015/16 and 2018/19 – cash terms

The reduction in Revenue Support Grant shown in Figure 1 has come alongside the introduction of 50 per cent business rates retention from 2013/14, meaning that some resources which might have been paid as grant are paid from business rates retained by local government as a whole. However, the Settlement Funding Assessment, which includes assumed business rates collected locally as well as Revenue Support Grant, has fallen by 26.7 per cent in the same period. [3]

Revenue Support Grant was due to have been phased out entirely with the introduction of further business rates retention, but this has now been postponed and will not happen in 2021. Further business rates retention would change the make-up of council funding, increasing potential rewards but also risks, such as losses in income due to business rates appeals.

Local authorities have little discretion over the bulk of their grant funding

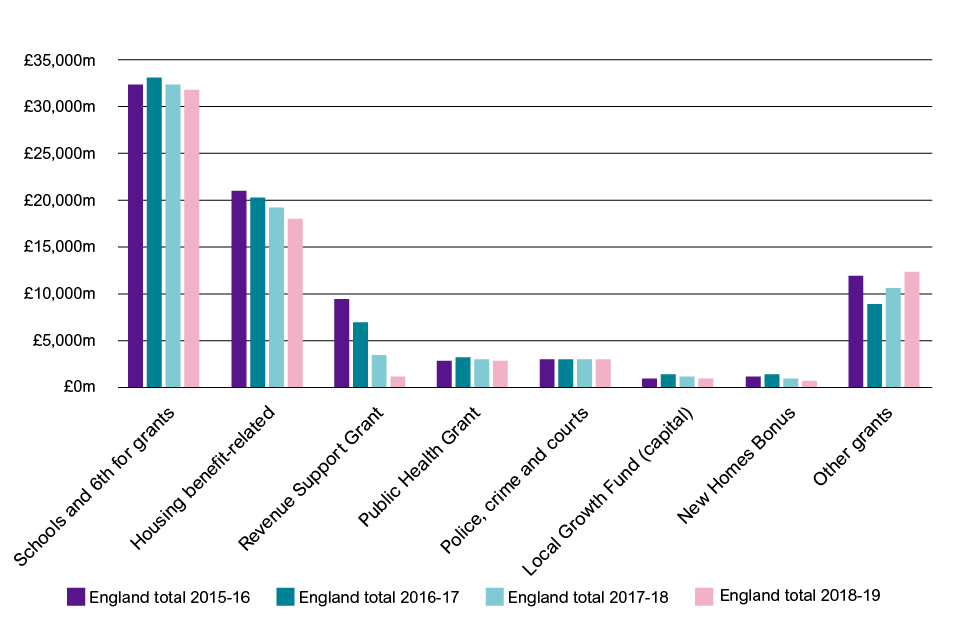

In the two biggest funding categories shown in figure two – schools and sixth-form grants and housing benefit grants – councils have very little discretion over expenditure.

Figure 2 Funding for English local authorities from 2015/16 to 2018/19

Grants for schools and sixth forms are passed by councils straight on to schools, and only a small proportion of housing benefit-related funding – the housing benefit administration grant – is used by councils to commission and deliver services. The vast majority is paid directly to tenants, with councils acting as delivery agents for central government.

Non-core grants are a disproportionate amount of grant funding

387, or 86 per cent, of the grants issued between 2015/16 and 2018/19 fall into the ‘other’ category, but this category of grants represented £12.43 billion in 2018/19 – only 17.8 per cent of total funding that year.

However, this includes the Improved Better Care Fund and Adult Social Care Support Grant. Once they are removed from this category, it represents only £10.847 billion, or 15.5 per cent of total funding.

Most of the grants issued to local government are small

Grants issued to local government vary widely in size. The largest are over £1 billion. However, over 50 grants – almost one quarter of those issued each year – are worth less than £1 million. Each of these grants equates to less than 0.25 per cent of the budget for a typical metropolitan district or London borough.

These grants are allocated to multiple councils, meaning the amount going to any given council is lower still.

Table 1 Numbers of grants of different sizes, 2015/16 to 2017/18

| Total value |

2015/16 |

2016/17 |

2017/19 |

| Under £1m |

58 |

54 |

54 |

| £1m-£10m |

69 |

67 |

71 |

| £10m-£100m |

66 |

57 |

69 |

| £100m-£500m |

33 |

31 |

35 |

| £500m or more |

22 |

21 |

21 |

Table 2 Percentage of grants of different sizes, 2015/16 to 2017/18

| Total value |

2015/16 |

2016/17 |

2017/19 |

| Under £1m |

23% |

23% |

22% |

| £1m-£10m |

28% |

29% |

28% |

| £10m-£100m |

27% |

25% |

28% |

| £100m-£500m |

13% |

13% |

14% |

| £500m or more |

9% |

9% |

8% |

A large proportion of the grants issued to local government are competitive

From our analysis of a sample of 366 grants [4], we found that almost one third are competitive – that is, councils are only able to access this funding by involvement in a competitive process. By comparison, 7 per cent were allocated to authorities which meet set criteria, and 28 per cent were awarded to councils using a formula.

Table 3 Grant allocation methods

| Allocation method - short name |

Number |

Percentage |

| Formula |

103 |

28% |

| Competed |

117 |

32% |

| Criteria-based |

27 |

7% |

| Un-competed |

83 |

23% |

| More than one allocation method |

36 |

20% |

| Total |

366 |

100% |

Local government funding is uncertain

Of the approximately 250 grants issued to councils each year between 2015/16 and 2018/19, over one third are discontinued from one year to the next. This includes grants intended for long-term capital projects.

The longevity of grants is often uncertain at the point when they are issued. Our analysis found that, of the 218 grants allocated to councils in 2017/18, over 90 per cent are listed as ending in the same year. However, in practice, two thirds of grants tend to continue onto the next year, which suggests that grants are recorded as ending in the same financial year by default.

Funding is fragmented across both services and departments

The grants issued to local government fall into 22 different service categories. Between 2015/16 and 2018/19, only 18 per cent of the grants issued were intended for more than one service area. The majority were for single, specific services.

These grants are in turn spread across a wide range of issuing bodies. In years analysed, 14 central government departments and 23 non-departmental public bodies issued funding to councils, with grants from agencies making up over one quarter of the total.

The quality of funding data is poor

Local government grant data is recorded across a large range of documents, with significant variations in the way that the details of local authorities and amounts distributed are recorded. As a result, not all departments – including MHCLG and HM Treasury – keep a full and accurate list of the grants provided to local government.

[3] Figures from MHCLG Core Spending Power information

[4] 366 grants (82 per cent of those in our database) were validated for analysis of allocation method, by cross-referencing this data between the Government Grants Register and other sources.