South Kesteven District Council’s mental health and wellbeing cross party working group worked in collaboration with health partners, a mental health charity and a community arts provider to investigate whether a local information resource would be useful to help reduce isolation and loneliness post Covid.

The challenge

Within a small town, how could we confidently engage with a delivery partner and produce robust evidence to inform a Wellbeing Map?

Funding to research need and local facilities and to commission Art Pop Up, a creative community arts organisation, was sourced via local mental health network partners. Art Pop Up was commissioned to work with our active partner Don’t Lose Hope, a mental health charity based in Bourne, Lincolnshire.

To meet funding timescales, there was an absolute need to work with trusted local partners: people known to the town with a reputation for delivering projects so that trust already existed for those interviewed and consulted during the research phase of the project.

Don’t Lose Hope carried out the research element, with Art Pop commissioned to produce the map because of its reputation for delivering quality community creative projects within other parts of the district.

The research focused on how people felt after the pandemic; attitudes towards mixing; engaging again with society and in groups and about how comfortable they felt doing that. It also looked at what people had been doing for their mental health during lockdown periods.

Research found that more people were doing solo based activities, 2 years post lockdown restrictions: reading, cycling, walking, crafting etc.

Data showed over 400 new activities (across the board with no trend on ages) were started as a result of the pandemic. Most used the time to “try new activities” both by starting online and learning through YouTube, groups and tutorials on social media. Although some now met in small peer groups that were established as a direct result of the new areas of interest, our challenge was how to provide the wider, still somewhat isolated population with information on local assets and opportunities for participation to bring them back together.

The solution

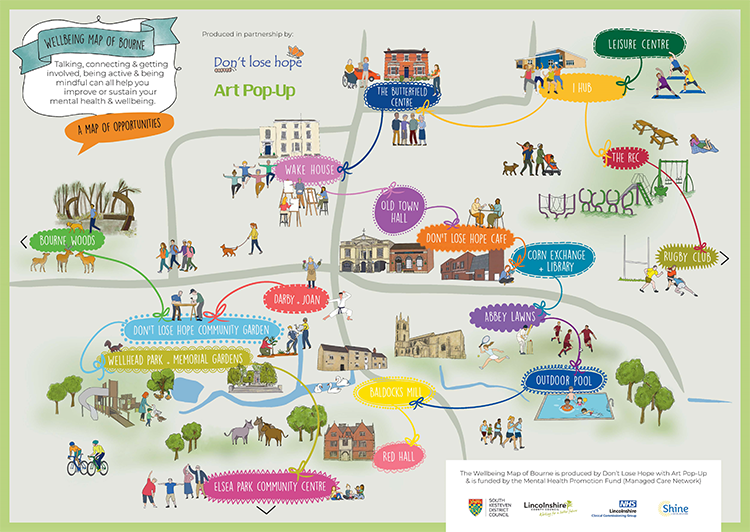

Our initial vision was to create a Wellbeing Map to illustrate what was available locally. We wanted to expand awareness of recreation activities and opportunities to meet other people with a common interest in both formal and informal settings.

As the project developed, it became apparent that our initial plan required adaptation to address some of the findings of the research. There was a need to add in activity to kick start behavioural change.

Despite restrictions being lifted for some time, it was clear the residual effects of lockdown meant that there remained a reluctance to interact.

Using the findings of the research: people’s new found enjoyment for walking, reading, crafting etc and the identification of local resources that would populate the Wellbeing Map, local groups set about establishing opportunities for people to come together – encouraged in by their new hobby and their willingness to learn from others. The research had identified that those who had taken up walking enjoyed the resulting “casual conversation” with others that became familiar faces along the way. Don’t Lose Hope therefore responded by offering opportunities for people to walk as a group. These opportunities remain informal - notification on social media of a walk that anyone is able to join – no need to book – just come along. The “casual conversations” along the way were now interwoven with information about other groups that people could join based on their interests. Now, they didn’t need to go alone (a barrier for many) – friends had been made along the way.

The impact

From the 125 interviews carried out as part of the research, 62 per cent were signposted to new groups.

On the whole, participants have reported increased engagement and increased personal wellbeing through social interaction as a result of simply taking part and feeling they were helping others.

People want to be able to look after their own mental health and wellbeing having been introduced to a broad range of groups and activities whilst chatting about what is on offer. The production of the Wellbeing Map helps people to identify places, facilities and organisations through which they can actively take care of their mental health and wellbeing.

The process of identifying community assets and bringing together the groups and organisations in the local area has resulted in the mental health and wellbeing provisions offered being more joined up with the opportunity for new collaborations to form. This in turn will enable an even broader offer.

The most significant impacts of this project – which set out to simply develop a physical resource to signpost people (the Wellbeing Map) are that it has brought groups and organisations together for the first time, all eager to work together for the greater good of their local area and that it has brought people together in a way that had reduced or no longer existed as a result of the Pandemic. Through the consultation, research and interaction with members of the public, opportunities for in person activity have been created, the continue to be delivered and will, most importantly, be sustained through community development interventions, by the very people they were put in place to support.

How is the new approach being sustained?

The original print version of the map will be maintained for those who need it in this format but, going forward, the map will also become digital, allowing for easy updates and ensuring the information provided remains relevant, up-to-date and fit for purpose.

It was clear from the launch event that there are many other charities, youth organisations and community assets that can already be added to broaden the map’s appeal and effectiveness.

Merely by engaging with existing organisations, our collaborators have enabled the development of a stronger network of grassroots partners, all eager to work together on projects to reduce social isolation and loneliness and thereby improving mental health and wellbeing.

National evidence shows that the mental health and wellbeing of young people has suffered greatly as a direct impact of the pandemic. We will, therefore, continue to work with local providers to link with some adult groups to explore opportunities to adapt existing provisions to support young people. The Wellbeing Map is merely the vehicle to information. Sustaining this asset is a simple process now that the initial work has been undertaken. The key to sustaining the project and the positive impact on mental health and wellbeing is the local providers. Collaboration amongst partners to keep delivering the offer of group activities and, through these activities, continuing to research the ever changing needs of a community. New opportunities for interaction and collaboration are still being identified.

Don’t Lose Hope has already spoken with a board gaming group, music groups and art groups at a local community venue to promote opportunities for young people

Lessons learned

Lessons learned in terms of the research stage include the fact that the research took longer than anticipated. Partners recognised that they underestimated the passion and desire people have to talk about their own groups and those they are involved with.

Where researchers envisaged a 15–30-minute conversation, some interviews lasted hours. This was an area where Don’t Lose Hope, as project lead, felt it was enlightening to see the pride local people had in their area and their determination to share as much detail and information as possible.

It is acknowledged that it would have been beneficial to keep track of respondents, following up after the initial consultation to determine whether they sought the support of the signposted activities and what they felt the effectiveness was of this signposting. Looking forward to future questionnaires this follow up will become an integral part of the process.

Evidence clearly showed that, despite the return to near normal living post the pandemic, some people, regardless of age and background remain reluctant to socialize and actively interact with others. Social isolation was forced upon people to protect them from harm during Covid but, for some, being socially isolated has become the new norm. This is not always a conscious decision but a subconscious often borne out of fear. Social isolation on the scale seen during and since the pandemic has fragmented communities and significantly impacted on the engagement and interaction of individuals. The biggest lesson learned is that, to bring communities back together, to help improve the mental health and wellbeing of individuals, is a long road and requires consistent, equitable support from charities, public sector organisations and community-based groups to be in place for many years to come.

Contact

Carol Drury, email: [email protected]